maximum test » Alexios "Emperor of Byzantium" Komnenos (1056-1118)

Persoonlijke gegevens Alexios "Emperor of Byzantium" Komnenos

- Roepnaam is Emperor of Byzantium.

- Hij is geboren in het jaar 1056 in Constantinople, Byzantine Empire.

- Beroepen:

- Keiser.

- Empereur, de Byzance.

- in het jaar 1081 unknown in Byzantine Emperor.

- Hij is overleden op 15 augustus 1118 in Constantinople, Byzantine Empire, hij was toen 62 jaar oud.

- Hij is begraven rond 1118 in Philanthropos, Greece.

- Een kind van Ioannes Κομνηνός en Anna Dalassene

- Deze gegevens zijn voor het laatst bijgewerkt op 12 april 2019.

Gezin van Alexios "Emperor of Byzantium" Komnenos

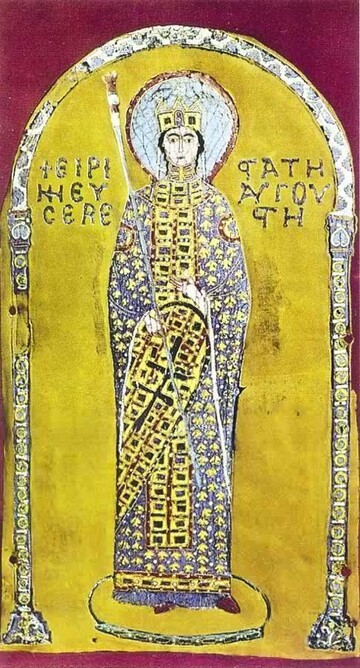

Hij is getrouwd met Irene Augusta Doukaina.

Zij zijn getrouwd rond januari 1078 te ConstantinopleIstanbul

Turkey.

Kind(eren):

Notities over Alexios "Emperor of Byzantium" Komnenos

GIVN Alexios I Emperorvom Byzantynischen

SURN Reich

REPO @REPO80@

TITL World Family Tree Vol. 11, Ed. 1

AUTH Brøderbund Software, Inc.

PUBL Release date: July 1, 1997

ABBR World Family Tree Vol. 11, Ed. 1

Customer pedigree.

Source Media Type: Family Archive CD

PAGE Tree #3804

DATA

TEXT Date of Import: 18 Dez 1998

REPO @REPO80@

TITL World Family Tree Vol. 11, Ed. 1

AUTH Brøderbund Software, Inc.

PUBL Release date: July 1, 1997

ABBR World Family Tree Vol. 11, Ed. 1

Customer pedigree.

Source Media Type: Family Archive CD

PAGE Tree #3804

DATA

TEXT Date of Import: 18 Dez 1998

REPO @REPO80@

TITL World Family Tree Vol. 11, Ed. 1

AUTH Brøderbund Software, Inc.

PUBL Release date: July 1, 1997

ABBR World Family Tree Vol. 11, Ed. 1

Customer pedigree.

Source Media Type: Family Archive CD

PAGE Tree #3804

DATA

TEXT Date of Import: 18 Dez 1998

DATE 9 SEP 2000

TIME 13:17:36

GIVN Alexios I Emperorvom Byzantynischen

SURN Reich

REPO @REPO80@

TITL World Family Tree Vol. 11, Ed. 1

AUTH Brøderbund Software, Inc.

PUBL Release date: July 1, 1997

ABBR World Family Tree Vol. 11, Ed. 1

Customer pedigree.

Source Media Type: Family Archive CD

PAGE Tree #3804

DATA

TEXT Date of Import: 18 Dez 1998

REPO @REPO80@

TITL World Family Tree Vol. 11, Ed. 1

AUTH Brøderbund Software, Inc.

PUBL Release date: July 1, 1997

ABBR World Family Tree Vol. 11, Ed. 1

Customer pedigree.

Source Media Type: Family Archive CD

PAGE Tree #3804

DATA

TEXT Date of Import: 18 Dez 1998

REPO @REPO80@

TITL World Family Tree Vol. 11, Ed. 1

AUTH Brøderbund Software, Inc.

PUBL Release date: July 1, 1997

ABBR World Family Tree Vol. 11, Ed. 1

Customer pedigree.

Source Media Type: Family Archive CD

PAGE Tree #3804

DATA

TEXT Date of Import: 18 Dez 1998

DATE 9 SEP 2000

TIME 13:17:36

Name Suffix:Byzantine Emperor

Keiser av Bysants 1081 - 1118.

Alexios var en fortreffelig feltherre som ble utropt til keiser av hæren 24.01.1081.

Han erobret Konstantinopel, hvoretter hans motstander Nikeforos gikk i kloster.

I 1081 ble han overvunnet ved Durazzo av Robert Guiscard, men da denne ble kalt

hjem til Apulia, ble hans etterlatte hær nesten tilintetgjort av Alexios. Robert angrep på ny i

1084, men døde i 1085.

Det første korstog til Jerusalem fant sted fra 1096 til 1099. Bakgrunnen var at den

hellige stad hadde falt i tyrkernes hender. Så lenge araberne var herrer i Jerusalem, hadde de

tatt godt imot pilegrimene, de så jo hvor mange penger det var å tjene på valfartene. Men

tyrkerne var så fanatiske muhammedanere at de ikke tålte å se kristne blandt seg. Da nå

pilegrimsskarene kom hjem fra Jerusalem og fortalte om hvordan tyrkerne hadde overfalt og

plyndret dem, om hvordan de hadde drevet gjøn med deres andaktsøvelser og til og med drept

flere pilegrimer, da steg det et skrik av forbitrelse mot de vantro fra hele Vesten.

Gotfred av Bouillon var den som først sto ferdig til oppbrudd for å dra til Bysants,

korsfarernes nærmeste felles mål. Snart var ikke mindre enn syv korstogshærer på vei dit.

Alexios likte seg ikke riktig da han fikk høre hva som var på ferde. Aldri hadde han tenkt seg at

han skulle bli så overveldende bønnhørt da han ba Den hellige fader om hjelp. Hva kunne

ikke disse, i hans øyne, halvt barbariske vesterlendingene under sine tøylesløse

krigerhøvdinger, komme til å finne på når de fikk se keiserbyens rike skatter! Det var ingen lett

oppgave å holde dem i godt humør og gjøre deres sverd til lydige redskaper for den bysantiske

politikk. Fremfor alt gjaldt det nå å hindre ethvert samarbeid mellom korsfarerhøvdingene før

han hadde fått dem vel over til Lilleasia. Alexios skjønte at han måtte underhandle med dem en

av gangen og lokke eller true dem til å avlegge lensed til keiseren for de erobringene de

eventuelt kom til å gjøre i Lilleasia og Syria, og deretter i tur og orden få dem over Bosporus så

snart som mulig.

Først gjaldt det altså Gotfred av Bouillon. Han nektet hårdnakket å anerkjenne keiseren

som sin lensherre, å gjøre seg til ?keiserens slave?, som han kalte det. Det begynte med at

han sa nei takk til keiserens innbydelse til å komme og hilse på ham. Gotfred aktet tydeligvis

først å avvente sine krigsfellers ankomst. Men det måtte for alt i verden ikke få skje. Alexios

grep derfor til det middel som etter hans mening var best egnet til å få korsfarerhøvdingen myk,

han avskar alle provianttilførsler. Hertugen svarte med å skaffe seg proviant selv med makt, og

keiseren måtte åpne for tilførslene igjen. Slik svinget begivenhetene fram og tilbake helt til

Gotfred av Bouillon innså at han i lengden måtte komme til å trekke det korteste strå i en

kraftprøve med keiseren. Nå fant han seg i å besøke Alexios i hans palass, bøye kne for

keiseren som satt på sin trone, og avlegge troskapsed til ham. Gotfred anerkjente dermed

Alexios som lensherre over alle de landområder han kom til å erobre i Østen. Orientalerens list

hadde seiret over vesterlendingens stolthet.

Deretter ble Gotfreds tropper transportert over Bosporus i god tid før Robert Guiscards

sønn, Bohemund av Tarent, ankom. Slik gjorde Alexios opp med den ene korsfarerhøvdingen

etter den andre og forvandlet dem så godt som alle sammen til lydige redskap for sine egne

planer før han satte dem over til den asiatiske siden av sundet. Med stor psykologisk

skarpsindighet behandlet han hver enkelt etter sin egenart. Ja, en av høvdingene skrev

begeistret hjem til sin hustru: ?Keiseren er som en far for meg; han elsker meg mer enn alle de

andre fyrstene. Og for en rikdom og en makt han har!? Med uovertreffelig mesterskap hadde

keiser Alexios tillempet den gamle romerske regelen: ?Divide et impera!?

Alexios styrte klokt og kraftig, og skaffet riket igjen herredømme over store deler av

Lilleasien. Alexios brakte orden i rikets indre forhold og beskyttet kirken. Hans liv er skildret i

?Alexiaden?.

Alexius I Comnenus

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Alexius I (Greek: ??????? ?' ??µ????? or Alexios I Komnenos) (1048 – August 15, 1118), Byzantine emperor (1081–1118), was the third son of John Comnenus, the nephew of Isaac I Comnenus (emperor 1057–1059).

His father declined the throne on the abdication of Isaac, who was accordingly succeeded by four emperors of other families between 1059 and 1081. Under one of these emperors, Romanus IV Diogenes (1067–1071), he served with distinction against the Seljuk Turks. Under Michael VII Parapinaces (1071–1078) and Nicephorus III Botaniates (1078–1081) he was also employed, along with his elder brother Isaac, against rebels in Asia Minor, Thrace and in Epirus in 1071.

The success of the Comneni roused the jealousy of Botaniates and his ministers, and the Comneni were almost compelled to take up arms in self-defence. Botaniates was forced to abdicate and retire to a monastery, and Isaac declined the crown in favour of his younger brother Alexius, who then became emperor at the age of 33.

By that time Alexius was the lover of the Empress Maria Bagrationi, a daughter of king Bagrat IV of Georgia who was successively married to Michael VII Ducas and his successor Botaniates, and was renowned for her beauty. Alexius and Maria lived almost openly together at the Palace of Mangana, and Alexius had Michael VII and Maria's young son, the prince Constantine Ducas, adopted and proclaimed heir to the throne. The affair conferred to Alexius a degree of dynastic legitimacy, but soon his mother Anna Dalassena consolidated the Ducas family connection by arranging the Emperor's wedding with Irene Ducaena or Doukaina, granddaughter of the caesar John Ducas, head of a powerful feudal family and the "kingmaker" behind Michael VII.

Alexius' involvement with Maria continued and shortly after his daughter Anna Comnena was born, she was betrothed to Constantine Ducas and moved to live at the Mangana Palace with him and Maria. The situation however changed drastically when John II Comnenus was born: Anna's engagement to Constantine was dissolved, she was moved to the main Palace to live with her mother and grandmother, Constantine's status as heir was terminated and Alexius became estranged with Maria, now stripped of her imperial title. Shortly afterwards, the teenager Constantine died and Maria was confined to a convent.

This coin was struck by Alexius during his war against Robert Guiscard.Alexius' long reign of nearly 37 years was full of struggle. At the very outset he had to meet the formidable attack of the Normans (Robert Guiscard and his son Bohemund), who took Dyrrhachium and Corfu, and laid siege to Larissa in Thessaly (see Battle of Dyrrhachium). The Norman danger ended for the time with Robert Guiscard's death in 1085, and the conquests were reversed.

He had next to repel the invasions of Pechenegs and Cumans in Thrace, with whom the Manichaean sect of the Bogomils made common cause; and thirdly, he had to cope with the fast-growing power of the Seljuk Turks in Asia Minor.

Above all he had to meet the difficulties caused by the arrival of the knights of the First Crusade, which had been, to a great degree, initiated as the result of the representations of his own ambassadors, whom he had sent to Pope Urban II at the Council of Piacenza in 1095. The help which he wanted from the West was simply mercenary forces and not the immense hosts which arrived, to his consternation and embarrassment. The first group, under Peter the Hermit, he dealt with by sending them on to Asia Minor, where they were massacred by the Turks in 1096.

The second and much more serious host of knights, led by Godfrey of Bouillon, he also led into Asia, promising to supply them with provisions in return for an oath of homage, and by their victories recovered for the Byzantine Empire a number of important cities and islands—Nicaea, Chios, Rhodes, Smyrna, Ephesus, Philadelphia, Sardis, and in fact most of Asia Minor (1097–1099). This is ascribed by his daughter Anna as a credit to his policy and diplomacy, but by the Latin historians of the crusade as a sign of his treachery and falseness. The crusaders believed their oaths were made invalid when Alexius did not help them during the siege of Antioch; Bohemund, who had set himself up as Prince of Antioch, briefly went to war with Alexius, but agreed to become Alexius' vassal under the Treaty of Devol in 1108.

During the last twenty years of his life he lost much of his popularity. The years were marked by persecution of the followers of the Paulician and Bogomil heresies—one of his last acts was to burn Basil, a Bogomil leader, with whom he had engaged in a theological controversy; by renewed struggles with the Turks (1110–1117); and by anxieties as to the succession, which his wife Irene wished to alter in favour of her daughter Anna's husband, Nicephorus Bryennius, for whose benefit the special title panhypersebastos ("honored above all") was created. This intrigue disturbed even his dying hours.

Alexius was for many years under the strong influence of an eminence grise, his mother Anna Dalassena, a wise and immensely able politician whom, in a uniquely irregular fashion, he had crowned as Empress Augusta instead of the rightful claimant to the title, his wife Irene. Dalassena was the effective administrator of the Empire during Alexius' long absences in war campaigns: she was constantly at odds with her daughter-in-law and had assumed total responsibility for the upbringing and education of her granddaughter Anna Comnena.

In 1078, when Nicephorus III Botaniates became Emperor, he made Alexius, who had defeated his rival, Bryennius, Domestic.

He was short but athletic, dark, handsome, dashing, gentle, shrewd, eloquent, talented, ambitious and strong-willed.

He was adopted by Maria the Alan, the second wife of Nicephorus III thereby making him the champion of the legitimacy of her son Constantine.

Warned by Maria that Nicephorus III was planning to blind them, Alexius and his brother, Issac, fled to the army of Thrace, where he was proclaimed Emperor and assaulted New Rome. Someone opened a gate, there was street fighting, pillage and massacre, which he was powerless to prevent. The Navy came over to Alexius and Nicephorus III abdicated and entered a monastery in 1081, indicating that his only regret was that future absence of meat from his diet!

He had attained the throne only with the support of many powerful factions. The treasury was empty, the army reduced, scattered and demoralized. He made peace with the Seljuks and enrolled 7000 of their warriors. When he decided to drive the Normans into the sea, he left the city and the palace under the control of his brother, and entrusted the government to his mother. He took the army to Durrazo, where the battle began in Oct., 1081. It looked as though he was winning, but then his Serbian and Turkish allies were bought of with Norman gold and withdrew from the field. Alexius and his courtiers seperated and fled.

Alone and hungry, he wandered over the mountains to Ochrida to try to gather another army, but their were no soldiers to be had. His family made great personal sacrifices, but the populace refused to cooperate as did the church. He invoked an ancient canon and pronounced the confiscation of the church's treasury.

When the leader of the Normans, Guiscard, died of an epidemic in 1085, that danger ended. In Apr., 1091, he annihilated the Patzinaks, and, returning in triumph, but childless, proclaimed Constantine Ducas his successor.

In 1095, Pope Urban II called on Christians to take up arms against Islam and free the Holy Sepulcher, thereby attaining complete atonement. While many sought only the remission of their sins, serfs also hoped to escape from bondage, adventurers to make fortunes and malefactors to evade punishment.

The first to depart were the poor, the People's Crusade of Peter the Hermit. Five groups marched east. The first two committed such excesses along the way that the Hungarians wiped them out. The third began to butcher Jews on the Rhine and was scattered by the Hungarians. But two hosts, led by Walter the Penniless and Peter the Hermit, reached New Rome in the summer of 1096.

Alexius recieved them with expedient forbearance, gave them food and money, and urged them to await the next contingent of Crusaders outside the city walls, but they began looting the suburbs, even sacking churches, so he sent them over to Civitot, a fort he had built in Turkey's shore. They continued to maraud, even torturing Christians. Soonthey began to ravage the Turkish countryside and 25,000 were killed. The imperial fleet brought the 3000 survivors back to New Rome to await the next Crusaders. These were already streaming eastward in plundering groups. Among them were Godfrey of Bouillon, who sought to exterminate the Jews in the German cities through which he passed, Raymond of Toulouse and Bohemund of Tarento. The advent of these armed hosts brought the danger of a sudden attack on the city. Though Alexius fed them, they too pillaged, killing all who resisted, including Orthodox priests. Alexius treated them with tact, patience and generosity, and moving through riot, arson, intrigue and insolence, obtained from most of the leaders the promise to restore to the Empire any land that had been hers before the Turkish invasion that they might conquer and to acknowledge him as suzerain for any further conquests. His success was probably due to their realization that his food, fleet, army and counsel were indispensible.

In the spring of 1097, they crossed to Anatolia. In 1098, when Antioch fell to Kerboga, many of them, including Stephen of Blois, fled and meeting Alexius, told him that it had certainly fallen, so being already overextended, he retreated.

Then Alexius was occupied with the arrival of four major grous of Crusaders from Italy, France Duitsland and Scandinavia who looted, murdered and even assaulted the city. He overlooked their misdeeds, exacted their recognition of him as overlord, and dispatched them against the Moslems, who made short work of them.

In 1112, in broken health, he took the field to battle the encroaching Turks once more.

When in 1118, he fell ill, to thwart the machinations of his wife, he gave his son John his ring, and bade him take over the realm.

Alexios I Komnenos, or Comnenus (Greek: ??????? ?' ??µ?????) (1048 - August 15, 1118), Byzantine emperor (1081-1118), was the son de Ioannis Komnenos and Anna Dalassena, and the nephew de Isaac I Komnenos (emperor 1057-1059). The military, financial, and territorial recovery de the Byzantine Empire began in his reign. His reign also witnessed the First Crusade which he used in order to reconquer these lands.

Alexius I Comnenus was the Byzantine emperor (from 1081to 1118) at the time of the First Crusade, who founded the Comnenian dynasty and partially restored the strength of the empire after its defeats by the Normans and Turks in the 11th century. The third son of John Comnenus and a nephew of Isaac I (emperor from 1057 to 1059), Alexius came of a distinguished Byzantine landed family and was one of the military magnates who had long urged more effective defense measures, particularly against the Turks' encroaching on Byzantine provinces in eastern and central Anatolia. From 1068 to 1081 he gave able military service during the short reigns of Romanus IV, Michael VII, and Nicephorus III. Then, with the support of his brother Isaac and his mother, the formidable Anna Dalassena, and with that of the powerful Ducas family, to which his wife, Irene, belonged, he seized the Byzantine throne from Nicephorus III. Alexius was crowned on April 4, 1081. After more than 50 years of ineffective or short-lived rulers, Alexius, in the words of Anna Comnena, his daughter and biographer, found the empire "at its last gasp", but his military ability and diplomatic gifts enabled him to retrieve the situation. He drove back the south Italian Normans, headed by Robert Guiscard, who were invading western Greece (in 1081and 1082). This victory was achieved with Venetian naval help, bought at the cost of granting Venice extensive trading privileges in the Byzantine Empire. In 1091 he defeated the Pechenegs, Turkic nomads who had been continually surging over the Danube River into the Balkans. Alexius halted the further encroachment of the Seljuq Turks, who had already established the Sultanate of Rum (or Konya) in central Anatolia. He made agreements with Sulayman ibn Qutalmïsh of Konya (in 1081) and subsequently with his son Qïlïch Arslan (in 1093), as well as with other Muslim rulers on Byzantium's eastern border. At home, Alexius' policy of strengthening the central authority and building up professional military and naval forces resulted in increased Byzantine strength in western and southern Anatolia and eastern Mediterranean waters. But he was unable or unwilling to limit the considerable powers of the landed magnates who had threatened the unity of the empire in the past. Indeed, he strengthened their position by further concessions, and he had to reward services, military and otherwise, by granting fiscal rights over specified areas. This method, which was to be increasingly employed by his successors, inevitably weakened central revenues and imperial authority. He repressed heresy and maintained the traditional imperial role of protecting the Eastern Orthodox church, but he did not hesitate to seize ecclesiastical treasure when in financial need. He was subsequently called to account for this by the church. To later generations Alexius appeared as the ruler who pulled the empire together at a crucial time, thus enabling it to survive until 1204, and in part until 1453, but modern scholars tend to regard him, together with his successors John II and Manuel I, as effecting only stopgap measures. But judgments of Alexius must be tempered by allowing for the extent to which he was handicapped by the inherited internal weaknesses of the Byzantine state and, even more, by the series of crises precipitated by the western European crusaders from 1097 onward. The crusading movement, motivated partly by a desire to recapture the holy city of Jerusalem, partly by the hope of acquiring new territory, increasingly encroached on Byzantine preserves and frustrated Alexius' foreign policy, which was primarily directed toward the reestablishment of imperial authority in Anatolia. His relations with Muslim powers were disrupted on occasion and former valued Byzantine possessions, such as Antioch, passed into the hands of arrogant Western princelings, who even introduced Latin Christianity in place of Greek. Thus, it was during Alexius' reign that the last phase of the clash between the Latin West and the Greek East was inaugurated. He did regain some control over western Anatolia; he also advanced into the southeast Taurus region, securing much of the fertile coastal plain around Adana and Tarsus, as well as penetrating farther south along the Syrian coast. But neither Alexius nor succeeding Comnenian emperors were able to establish permanent control over the Latin crusader principalities. Nor was the Byzantine Empire immune from further Norman attacks on its western islands and provinces - as in 1107 to 1108, when Alexius successfully repulsed Bohemond I of Antioch's assault on Avlona in western Greece. Continual Latin (particularly Norman) attacks, constant thrusts from Muslim principalities, the rising power of Hungary and the Balkan principalities - all conspired to surround Byzantium with potentially hostile forces. Even Alexius' diplomacy, whatever its apparent success, could not avert the continual erosion that ultimately led to the Ottoman conquest. Alexius I Comnenus. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved June 26, 2003, from Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia.

(Redirected from Alexius I)

Byzantine emperor Alexius I ComnenusAlexius I (1048–August 15, 1118),Byzantine emperor (1081–1118), was the third son of John Comnenus,nephew of Isaac I Comnenus (emperor 1057–1059).

His father declined the throne on the abdication of Isaac, who wasaccordingly succeeded by four emperors of other families between 1059and 1081. Under one of these emperors, Romanus IV Diogenes(1067–1071), he served with distinction against the Seljuk Turks.Under Michael VII Parapinaces (1071–1078) and Nicephorus IIIBotaniates (1078–1081) he was also employed, along with his elderbrother Isaac, against rebels in Asia Minor, Thrace and in Epirus in1071.

The success of the Comneni roused the jealousy of Botaniates and hisministers, and the Comneni were almost compelled to take up arms inself-defence. Botaniates was forced to abdicate and retire to amonastery, and Isaac declined the crown in favour of his youngerbrother Alexius, who then became emperor at the age of 33.

His long reign of nearly 37 years was full of struggle. At the veryoutset he had to meet the formidable attack of the Normans (RobertGuiscard and his son Bohemund), who took Dyrrhachium and Corfu, andlaid siege to Larissa in Thessaly (see Battle of Dyrrhachium). TheNorman danger ended for the time with Robert Guiscard's death in 1085,and the conquests were reversed.

He had next to repel the invasions of Pechenegs and Cumans in Thrace,with whom the Manichaean sect of the Bogomils made common cause; andthirdly, he had to cope with the fast-growing power of the SeljukTurks in Asia Minor.

Above all he had to meet the difficulties caused by the arrival of theknights of the First Crusade, which had been, to a great degree,initiated as the result of the representations of his own ambassadors,whom he had sent to Pope Urban II at the Council of Piacenza in 1095.The help which he wanted from the West was simply mercenary forces andnot the immense hosts which arrived, to his consternation andembarrassment. The first group, under Peter the Hermit, he dealt withby sending them on to Asia Minor, where they were massacred by theTurks in 1096.

The second and much more serious host of knights, led by Godfrey ofBouillon, he also led into Asia, promising to supply them withprovisions in return for an oath of homage, and by their victoriesrecovered for the Byzantine Empire a number of important cities andislands—Nicaea, Chios, Rhodes, Smyrna, Ephesus, Philadelphia, Sardis,and in fact most of Asia Minor (1097–1099). This is ascribed by hisdaughter Anna as a credit to his policy and diplomacy, but by theLatin historians of the crusade as a sign of his treachery andfalseness. The crusaders believed their oaths were made invalid whenAlexius did not help them during the siege of Antioch; Bohemund, whohad set himself up as Prince of Antioch, briefly went to war withAlexius, but agreed to become Alexius' vassal under the Treaty ofDevol in 1108.

During the last twenty years of his life he lost much of hispopularity. The years were marked by persecution of the followers ofthe Paulician and Bogomil heresies—one of his last acts was to burnBasilius, a Bogomil leader, with whom he had engaged in a theologicalcontroversy; by renewed struggles with the Turks (1110–1117); and byanxieties as to the succession, which his wife Irene wished to alterin favour of her daughter Anna's husband, Nicephorus Bryennius, forwhose benefit the special title panhypersebastos ("honored above all")was created. This intrigue disturbed even his dying hours.

He deserves the credit for having saved the Empire from a condition ofanarchy and decay at a time when it was threatened on all sides by newdangers. No emperor devoted himself more laboriously, or with agreater sense of duty, to the task of ruling.

(ref: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexius_I_Comnenus) Alexios I Komne nos (1048 - August 15, 1118), Byzantine emperor (1081 - 1118), was th e nephew of Isaac I Komnenos (emperor 1057 - 1059), being the third so n of that emperor's brother John Komnenos. The military, financial an d territorial recovery of the Byzantine Empire known as Komnenian rest oration began in his reign. His father declined the throne on the abd ication of Isaac, who was accordingly succeeded by four emperors of ot her families between 1059 and 1081. Under one of these emperors, Roman os IV Diogenes (1067 - 1071), he served with distinction against the S eljuk Turks. Under Michael VII Doukas Parapinakes (1071 - 1078) and Ni kephoros III Botaneiates (1078 - 1081) he was also employed, along wit h his elder brother Isaac, against rebels in Asia Minor, Thrace and i n Epirus.

In 1074 Alexios successfully subdued the rebel mercenaries in Asia Min or, and in 1078 he was appointed commander of the field army in the We st by Nikephoros III. In this capacity Alexios defeated the rebellion s of two successive governors of Dyrrhachium, Nikephoros Bryennios (wh ose son or grandson later married Alexios' daughter Anna), and Nikepho ros Basilakes. Alexios was ordered to march against his brother-in-la w Nikephoros Melissenos in Asia Minor, but refused to fight his kinsma n. This did not, however, lead to a demotion, as Alexios was needed t o counter the expected Norman invasion led by Robert Guiscard near Dyr rhachium. While the Byzantine troops were assembling for the expediti on, Alexios was approached by the Doukas faction at court, who convinc ed him to join a conspiracy against Nikephoros III. Alexios was duly p roclaimed emperor by his troops and marched on Constantinople. Bribin g the western mercenaries guarding the city, the rebels entered Consta ntinople in triumph, meeting little resistance on April 1, 1081. Nikep horos III was forced to abdicate and retire to a monastery, and Patria rch Kosmas I crowned Alexios I emperor on April 4.

By that time Alexios was the lover of the Empress Maria of Alania, th e daughter of King Bagrat IV of Georgia who had been successively marr ied to Michael VII Doukas and his successor Nikephoros III Botaneiates , and was renowned for her beauty. Alexios and Maria lived almost open ly together at the Palace of Mangana. However, Alexios did not marry t he empress. His mother Anna Dalassena consolidated the Doukas family c onnection by arranging the Emperor's marriage to Irene Doukaina, grand daughter of the Caesar John Doukas, the uncle of Michael VII. As a mea sure intended to keep the support of the Doukai, Alexios restored Cons tantine Doukas, the young son of Michael VII and Maria, as co-emperora nd a little later betrothed him to his own first-born daughter Anna,wh o moved into the Mangana Palace with her husband and his mother.

However, this situation changed drastically when Alexios' first son Jo hn II Komnenos was born in 1187: Anna's engagement to Constantine wasd issolved and she was moved to the main Palace to live with her mother and grandmother. Alexios became estranged from Maria, who was strippe d of her imperial title and retired to a monastery, and Constantine Do ukas was deprived of his status as co-emperor. Nevertheless he remaine d in good relations with the imperial family and succumbed to his wea k constitution soon afterwards.

This coin was struck by Alexios during his war against Robert Guiscard .Alexios' long reign of nearly 37 years was full of struggle. At the v ery outset he had to meet the formidable attack of the Normans (led b y Robert Guiscard and his son Bohemund), who took Dyrrhachium and Corf u, and laid siege to Larissa in Thessaly (see Battle of Dyrrhachium).A lexios suffered several defeats before being able to strike back with success. He enhanced this by bribing the German king Henry IV to attac k the Normans in Italy, which forced the Normans to concentrate on the ir defenses at home in 1083–1084. The Norman danger ended for the tim e being with Robert Guiscard's death in 1085, and the Byzantines recov ered most of their losses.

Alexios had next to deal with disturbances in Thrace, where the hereti cal sects of the Bogomils and the Paulicians revolted and made commonc ause with the Pechenegs from beyond the Danube. Paulician soldiers in imperial service likewise deserted during Alexios' battles with theNor mans. As soon as the Norman threat had passed, Alexios set out to puni sh the rebels and deserters, confiscating their lands. This led toa fu rther revolt near Philippopolis (Plovdiv), and the commander of the fi eld army in the west, Gregory Pakourianos, was defeated and killed in the ensuing battle. In 1087 the Pechenegs raided into Thrace andAlexio s crossed into Moesia to retaliate but failed to take Dorostolon (Sili stra). During his retreat, the emperor was surrounded and worndown by the Pechenegs, who forced him to sign a truce and pay protection money . In 1090 the Pechenegs invaded Thrace again, while the brother-in-la w of the Sultan of Rum launched a fleet and attempted to arrange a joi ng siege of Constantinople with the Pechenegs. Alexios overcame this c risis by entering into an alliance with a horde of 40,000 Cumans, wit h whose help he crushed the Pechenegs at Levounion in Thrace on April 29, 1091. This put an end to the Pecheneg threat, but in 1094 the Cum ans began to raid the imperial territories in the Balkans. Led by a pr etender claiming to be Constantine Diogenes, a long-dead sonof the Emp eror Romanos IV, the Cumans crossed the mountains and raided into east ern Thrace until their leader was eliminated at Adrianople. With the B alkans more or less pacified, Alexios could now turn his attention to Asia Minor, which had been almost completely overrun by the Seljuk Tur ks.

As early as 1090, Alexios had taken reconciliatory measures towards th e Papacy, with the intention of seeking western support against the Se ljuks. In 1095 his ambassadors appeared before Pope Urban II at the Co uncil of Piacenza. The help which he wanted from the West was simply m ercenary forces and not the immense hosts which arrived, to his conste rnation and embarrassment, after the pope preached the First Crusade a t the Council of Clermont later that same year. Not quite ready to sup ply this number of people as they traversed his territories, the emper or saw his Balkan possessions subjected to further pillage at the hand s of his own allies. Alexios dealt with the first disorganized group o f crusaders, led by the preacher Peter the Hermit, by sending them ont o Asia Minor, where they were massacred by the Turks in 1096.

The second and much more formidable host of crusaders gradually made i ts way to Constantinople, led in sections by Godfrey of Bouillon, Bohe mund of Taranto, Raymond IV of Toulouse and other important members o f the western nobility. Alexios used the opportunity of meeting the cr usader leaders separately as they arrived and extracting from them oat hs of homage and the promise to turn over conquered lands to the Byzan tine Empire. Transferring each contingent into Asia, Alexios promisedt o supply them with provisions in return for their oaths of homage. Th e crusade was a notable success for Byzantium, as Alexios now recovere d for the Byzantine Empire a number of important cities and islands. T he crusader siege of Nicaea forced the city to surrender to the empero r in 1097, and the subsequent crusader victory at Dorylaion allowed th e Byzantine forces to recover much of western Asia Minor. Here Byzanti ne rule was reestablished in Chios, Rhodes, Smyrna, Ephesus, Philadelp hia, and Sardis in 1097 - 1099. This success is ascribed by his daught er Anna to his policy and diplomacy, but by the Latin historians of th e crusade to his treachery and falseness. The crusaders believed thei r oaths were made invalid when the Byzantine contingent under Tatikio s failed to help them during the siege of Antioch; Bohemund, who had s et himself up as Prince of Antioch, briefly went to war with Alexios i n the Balkans, but was blockaded by the Byzantine forces and agreed t o become Alexios' vassal by the Treaty of Devol in 1108.

During the last twenty years of his life Alexios lost much of his popu larity. The years were marked by persecution of the followers of the P aulician and Bogomil heresies—one of his last acts was to publicly bur n on the stake Basil, a Bogomil leader, with whom he had engaged in at heological dispute. In spite of the success of the crusade, Alexios al so had to repel numerous attempts on his territory by the Seljuks in11 10 - 1117.

Alexios was for many years under the strong influence of an eminence g rise, his mother Anna Dalassene, a wise and immensely able politicianw hom, in a uniquely irregular fashion, he had crowned as Augusta instea d of the rightful claimant to the title, his wife Irene Doukaina. Dala ssena was the effective administrator of the Empire during Alexius' lo ng absences in military campaigns: she was constantly at odds with he r daughter-in-law and had assumed total responsibility for the upbring ing and education of her granddaughter Anna Komnene. Alexios' last ye ars were also troubles by anxieties over the succession. Although he h ad crowned his son John II Komnenos co-emperor at the age of 5 in 1092 , John's mother Irene Doukaina wished to alter the succession in favo r of her daughter Anna and Anna's husband, Nikephoros Bryennios. Bryen nios had been made kaisar (Caesar) and received the newly-created titl e of panhypersebastos ("honored above all"), and remained loyal to bot h Alexios and John. Nevertheless, the intrigues of Irene and Anna dist urbed even Alexios' dying hours.

Alexios I had stablized the Byzantine Empire and overcome a dangerousc risis, inaugurating a century of imperial prosperity and success. Heha d also profoundly altered the nature of the Byzantine government. By s eeking close alliances with powerful noble families, Alexios put an en d to the tradition of imperial exclusivity and coopted most of the nob ility into his extended family and, through it, his government. This m easure, which was intended to diminish opposition, was paralleled by t he introduction of new courtly dignities, like that of panhypersebasto s given to Nikephoros Bryennios, or that of sebastokrator givento the emperor's brother Isaac Komnenos. Although this policy met with initia l success, it gradually undermined the relative effectivenessof imperi al bureacracy by placing family connections over merit. Alexios' polic y of integration of the nobility bore the fruit of continuity: every B yzantine emperor who reigned after Alexios I Komnenos was related to h im by either descent or marriage.

By his marriage with Irene Doukaina, Alexios I had the following child ren: 1.) Anna Komnene, who married the Caesar Nikephoros Bryennios; 2. ) Maria Komnene, who married (1) Gregory Gabras and (2) Nikephoros Eup horbenos Katakalon; 3.) John II Komnenos, who succeeded as emperor; 4. ) Andronikos Komnenos, sebastokrator; 5.) Isaac Komnenos, sebastokrato r; 6.) Eudokia Komnene, who married Michael Iasites; 7.) Theodora Komn ene, who married (1) Constantine Kourtikes and (2) Constantine Angelos . By him she was the grandmother of Emperors Isaac II Angelos and Alex ios III Angelos.

Manuel Komnenos; and 8.)Zoe Komnene.

GIVN Alexios I Emperorvom Byzantynischen

SURN Reich

REPO @REPO80@

TITL World Family Tree Vol. 11, Ed. 1

AUTH Brøderbund Software, Inc.

PUBL Release date: July 1, 1997

ABBR World Family Tree Vol. 11, Ed. 1

Customer pedigree.

Source Media Type: Family Archive CD

PAGE Tree #3804

DATA

TEXT Date of Import: 18 Dez 1998

REPO @REPO80@

TITL World Family Tree Vol. 11, Ed. 1

AUTH Brøderbund Software, Inc.

PUBL Release date: July 1, 1997

ABBR World Family Tree Vol. 11, Ed. 1

Customer pedigree.

Source Media Type: Family Archive CD

PAGE Tree #3804

DATA

TEXT Date of Import: 18 Dez 1998

REPO @REPO80@

TITL World Family Tree Vol. 11, Ed. 1

AUTH Brøderbund Software, Inc.

PUBL Release date: July 1, 1997

ABBR World Family Tree Vol. 11, Ed. 1

Customer pedigree.

Source Media Type: Family Archive CD

PAGE Tree #3804

DATA

TEXT Date of Import: 18 Dez 1998

DATE 9 SEP 2000

TIME 13:17:36

[Jeremiah Brown.FTW]

[from Rootsweb jerryc490 database]

Alexius I COMNENUS (b. 1048, Constantinople [now Istanbul, Tur.]--d. Aug. 15, 1118), Byzantine emperor (1081-1118) at the time of the First Crusade, who founded the Comnenian dynasty and partially restored the strength of the empire after its defeats by the Normans and Turks in the 11th century.

The third son of John Comnenus and a nephew of Isaac I (emperor 1057-59), Alexius came of a distinguished Byzantine landed family and was one of the military magnates who had long urged more effective defense measures, particularly against the Turks' encroaching on Byzantine provinces in eastern and central Anatolia. From 1068 to 1081 he gave able military service during the short reigns of Romanus IV, Michael VII, and Nicephorus III. Then, with the support of his brother Isaac and his mother, the formidable Anna Dalassena, and with that of the powerful Ducas family, to which his wife, Irene, belonged, he seized the Byzantine throne from Nicephorus III.

Alexius was crowned on April 4, 1081. After more than 50 years of ineffective or short-lived rulers, Alexius, in the words of Anna Comnena, his daughter and biographer, found the empire "at its last gasp," but his military ability and diplomatic gifts enabled him to retrieve the situation. He drove back the south Italian Normans, headed by Robert Guiscard, who were invading western Greece (1081-82). This victory was achieved with Venetian naval help, bought at the cost of granting Venice extensive trading privileges in the Byzantine Empire. In 1091 he defeated the Pechenegs, Turkic nomads who had been continually surging over the Danube River into the Balkans. Alexius halted the further encroachment of the Seljuq Turks, who had already established the Sultanate of Rum (or Konya) in central Anatolia. He made agreements with Sulayman ibn Qutalmïsh of Konya (1081) and subsequently with his son Qïlïch Arslan (1093), as well as with other Muslim rulers on Byzantium's eastern border.

At home, Alexius' policy of strengthening the central authority and building up professional military and naval forces resulted in increased Byzantine strength in western and southern Anatolia and eastern Mediterranean waters. But he was unable or unwilling to limit the considerable powers of the landed magnates who had threatened the unity of the empire in the past. Indeed, he strengthened their position by further concessions, and he had to reward services, military and otherwise, by granting fiscal rights over specified areas. This method, which was to be increasingly employed by his successors, inevitably weakened central revenues and imperial authority. He repressed heresy and maintained the traditional imperial role of protecting the Eastern Orthodox church, but he did not hesitate to seize ecclesiastical treasure when in financial need. He was subsequently called to account for this by the church.

To later generations Alexius appeared as the ruler who pulled the empire together at a crucial time, thus enabling it to survive until 1204, and in part until 1453, but modern scholars tend to regard him, together with his successors John II (reigned 1118-43) and Manuel I (reigned 1143-80), as effecting only stopgap measures. But judgments of Alexius must be tempered by allowing for the extent to which he was handicapped by the inherited internal weaknesses of the Byzantine state and, even more, by the series of crises precipitated by the western European crusaders from 1097 onward. The crusading movement, motivated partly by a desire to recapture the holy city of Jerusalem, partly by the hope of acquiring new territory, increasingly encroached on Byzantine preserves and frustrated Alexius' foreign policy, which was primarily directed toward the reestablishment of imperial authority in Anatolia. His relations with Muslim powers were disrupted on occasion and former valued Byzantine possessions, such as Antioch, passed into the hands of arrogant Western princelings, who even introduced Latin Christianity in place of Greek. Thus, it was during Alexius' reign that the last phase of the clash between the Latin West and the Greek East was inaugurated. He did regain some control over western Anatolia; he also advanced into the southeast Taurus region, securing much of the fertile coastal plain around Adana and Tarsus, as well as penetrating farther south along the Syrian coast. But neither Alexius nor succeeding Comnenian emperors were able to establish permanent control over the Latin crusader principalities. Nor was the Byzantine Empire immune from further Norman attacks on its western islands and provinces--as in 1107-08, when Alexius successfully repulsed Bohemond I of Antioch's assault on Avlona in western Greece. Continual Latin (particularly Norman) attacks, constant thrusts from Muslim principalities, the rising power of Hungary and the Balkan principalities--all conspired to surround Byzantium with potentially hostile forces. Even Alexius' diplomacy, whatever its apparent success, could not avert the continual erosion that ultimately led to the Ottoman conquest. [Encyclopaedia Britannica CD '97]

{geni:about_me} https://fi.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aleksios_I_Komnenos

http://www.friesian.com/romania.htm#comneni

http://genealogics.org/getperson.php?personID=I00049915&tree=LEO

Alexios I Komnenos, or Comnenus (Greek: Αλέξιος Α' Κομνηνός) (1048 – August 15, 1118), Byzantine emperor (1081–1118), was the son of John Comnenus and Anna Dalassena and the nephew of Isaac I Comnenus (emperor 1057–1059). The military, financial and territorial recovery of the Byzantine Empire began in his reign.

Contents

1 Life

1.1 Byzantine-Norman Wars

1.2 Byzantine-Seljuk Wars

1.3 Personal life

1.4 Succession

2 Legacy

3 Family

4 References

5 External links

Life

Alexius' father declined the throne on the abdication of Isaac, who was accordingly succeeded by four emperors of other families between 1059 and 1081. Under one of these emperors, Romanus IV Diogenes (1067–1071), he served with distinction against the Seljuk Turks. Under Michael VII Ducas Parapinaces (1071–1078) and Nicephorus III Botaneiates (1078–1081), he was also employed, along with his elder brother Isaac, against rebels in Asia Minor, Thrace and in Epirus.

Alexius' mother wielded great influence during his reign, and he is described by his daughter, the historian Anna Comnena, as running next to the imperial chariot that she drove. In 1074, the rebel mercenaries in Asia Minor were successfully subdued, and, in 1078, he was appointed commander of the field army in the West by Nicephorus III. In this capacity, Alexius defeated the rebellions of two successive governors of Dyrrhachium, Nicephorus Bryennius (whose son or grandson later married Alexius' daughter Anna) and Nicephorus Basilakes. Alexius was ordered to march against his brother-in-law Nicephorus Melissenus in Asia Minor but refused to fight his kinsman. This did not, however, lead to a demotion, as Alexius was needed to counter the expected Norman invasion led by Robert Guiscard near Dyrrhachium.

While the Byzantine troops were assembling for the expedition, Alexius was approached by the Ducas faction at court, who convinced him to join a conspiracy against Nicephorus III. Alexius was duly proclaimed emperor by his troops and marched on Constantinople. Bribing the western mercenaries guarding the city, the rebels entered Constantinople in triumph, meeting little resistance on April 1, 1081. Nicephorus III was forced to abdicate and retire to a monastery, and Patriarch Cosmas I crowned Alexius I emperor on April 4.

During this time, Alexius was rumored to be the lover of Empress Maria of Alania, the daughter of King Bagrat IV of Georgia, who had been successively married to Michael VII Ducas and his successor Nicephorus III Botaneiates, and was renowned for her beauty. Alexius arranged for Maria to stay on the palace grounds. It was also thought that Alexius may have been considering marrying the erstwhile empress. However, his mother consolidated the Ducas family connection by arranging the Emperor's marriage to Irene Ducaena, granddaughter of the Caesar John Ducas, the uncle of Michael VII, who would not have supported Alexius otherwise. As a measure intended to keep the support of the Ducae, Alexius restored Constantine Ducas, the young son of Michael VII and Maria, as co-emperor and a little later betrothed him to his own first-born daughter Anna, who moved into the Mangana Palace with her fiancé and his mother.

However, this situation changed drastically when Alexius' first son John II Comnenus was born in 1087: Anna's engagement to Constantine was dissolved, and she was moved to the main Palace to live with her mother and grandmother. Alexius became estranged from Maria, who was stripped of her imperial title and retired to a monastery, and Constantine Ducas was deprived of his status as co-emperor. Nevertheless, he remained in good relations with the imperial family and succumbed to his weak constitution soon afterwards.

This coin was struck by Alexius during his war against Robert Guiscard.

Byzantine-Norman Wars

Alexius' long reign of nearly thirty-seven years was full of struggle. At the very outset, he had to meet the formidable attack of the Normans (led by Robert Guiscard and his son Bohemund), who took Dyrrhachium and Corfu, and laid siege to Larissa in Thessaly (see Battle of Dyrrhachium). Alexius suffered several defeats before being able to strike back with success. He enhanced this by bribing the German king Henry IV with 360,000 gold pieces to attack the Normans in Italy, which forced the Normans to concentrate on their defenses at home in 1083–1084. He also secured the alliance of Henry, Count of Monte Sant'Angelo, who controlled the Gargano Peninsula and dated his charters by Alexius' reign. Henry's allegiance was to be the last example of Byzantine political control on peninsular Italy. The Norman danger ended for the time being with Robert Guiscard's death in 1085, and the Byzantines recovered most of their losses.

Alexius had next to deal with disturbances in Thrace, where the heretical sects of the Bogomils and the Paulicians revolted and made common cause with the Pechenegs from beyond the Danube. Paulician soldiers in imperial service likewise deserted during Alexius' battles with the Normans. As soon as the Norman threat had passed, Alexius set out to punish the rebels and deserters, confiscating their lands. This led to a further revolt near Philippopolis, and the commander of the field army in the west, Gregory Pakourianos, was defeated and killed in the ensuing battle. In 1087 the Pechenegs raided into Thrace and Alexius crossed into Moesia to retaliate but failed to take Dorostolon (Silistra). During his retreat, the emperor was surrounded and worn down by the Pechenegs, who forced him to sign a truce and pay protection money. In 1090 the Pechenegs invaded Thrace again, while the brother-in-law of the Sultan of Rum launched a fleet and attempted to arrange a joing siege of Constantinople with the Pechenegs. Alexius overcame this crisis by entering into an alliance with a horde of 40,000 Cumans, with whose help he crushed the Pechenegs at Levounion in Thrace on April 29, 1091.

The Byzantine Empire at the accession of Alexius I Comnenus, c. 1081

This put an end to the Pecheneg threat, but in 1094 the Cumans began to raid the imperial territories in the Balkans. Led by a pretender claiming to be Constantine Diogenes, a long-dead son of the Emperor Romanos IV, the Cumans crossed the mountains and raided into eastern Thrace until their leader was eliminated at Adrianople. With the Balkans more or less pacified, Alexius could now turn his attention to Asia Minor, which had been almost completely overrun by the Seljuk Turks.

Byzantine-Seljuk Wars

As early as 1090, Alexius had taken reconciliatory measures towards the Papacy, with the intention of seeking western support against the Seljuks. In 1095 his ambassadors appeared before Pope Urban II at the Council of Piacenza. The help which he wanted from the West was simply mercenary forces and not the immense hosts which arrived, to his consternation and embarrassment, after the pope preached the First Crusade at the Council of Clermont later that same year. Not quite ready to supply this number of people as they traversed his territories, the emperor saw his Balkan possessions subjected to further pillage at the hands of his own allies. Alexius dealt with the first disorganized group of crusaders, led by the preacher Peter the Hermit, by sending them on to Asia Minor, where they were massacred by the Turks in 1096.

The second and much more formidable host of crusaders gradually made its way to Constantinople, led in sections by Godfrey of Bouillon, Bohemund of Taranto, Raymond IV of Toulouse and other important members of the western nobility. Alexius used the opportunity of meeting the crusader leaders separately as they arrived and extracting from them oaths of homage and the promise to turn over conquered lands to the Byzantine Empire. Transferring each contingent into Asia, Alexius promised to supply them with provisions in return for their oaths of homage. The crusade was a notable success for Byzantium, as Alexius now recovered for the Byzantine Empire a number of important cities and islands. The crusader siege of Nicaea forced the city to surrender to the emperor in 1097, and the subsequent crusader victory at Dorylaion allowed the Byzantine forces to recover much of western Asia Minor. Here Byzantine rule was reestablished in Chios, Rhodes, Smyrna, Ephesus, Sardis, and Philadelphia in 1097–1099. This success is ascribed by his daughter Anna to his policy and diplomacy, but by the Latin historians of the crusade to his treachery and falseness. In 1099, a Byzantine fleet of 10 ships were sent to assist the Crusaders in capturing Laodicea and other coastal towns as far as Tripoli. The crusaders believed their oaths were made invalid when the Byzantine contingent under Tatikios failed to help them during the siege of Antioch; Bohemund, who had set himself up as Prince of Antioch, briefly went to war with Alexius in the Balkans, but was blockaded by the Byzantine forces and agreed to become Alexius' vassal by the Treaty of Devol in 1108.

Personal life

During the last twenty years of his life Alexius lost much of his popularity. The years were marked by persecution of the followers of the Paulician and Bogomil heresies—one of his last acts was to publicly burn on the stake Basil, a Bogomil leader, with whom he had engaged in a theological dispute. In spite of the success of the crusade, Alexius also had to repel numerous attempts on his territory by the Seljuks in 1110–1117.

Alexius was for many years under the strong influence of an eminence grise, his mother Anna Dalassena, a wise and immensely able politician whom, in a uniquely irregular fashion, he had crowned as Augusta instead of the rightful claimant to the title, his wife Irene Ducaena. Dalassena was the effective administrator of the Empire during Alexius' long absences in military campaigns: she was constantly at odds with her daughter-in-law and had assumed total responsibility for the upbringing and education of her granddaughter Anna Comnena.

Succession

Alexius' last years were also troubled by anxieties over the succession. Although he had crowned his son John II Comnenus co-emperor at the age of five in 1092, John's mother Irene Doukaina wished to alter the succession in favor of her daughter Anna and Anna's husband, Nicephorus Bryennius. Bryennios had been made kaisar (Caesar) and received the newly-created title of panhypersebastos ("honoured above all"), and remained loyal to both Alexius and John. Nevertheless, the intrigues of Irene and Anna disturbed even Alexius' dying hours.

Legacy

Alexius I had stabilized the Byzantine Empire and overcome a dangerous crisis, inaugurating a century of imperial prosperity and success. He had also profoundly altered the nature of the Byzantine government. By seeking close alliances with powerful noble families, Alexius put an end to the tradition of imperial exclusivity and coopted most of the nobility into his extended family and, through it, his government. This measure, which was intended to diminish opposition, was paralleled by the introduction of new courtly dignities, like that of panhypersebastos given to Nicephorus Bryennius, or that of sebastokrator given to the emperor's brother Isaac Comnenus. Although this policy met with initial success, it gradually undermined the relative effectiveness of imperial bureaucracy by placing family connections over merit. Alexius' policy of integration of the nobility bore the fruit of continuity: every Byzantine emperor who reigned after Alexius I Comnenus was related to him by either descent or marriage.

Family

By his marriage with Irene Ducaena, Alexius I had the following children:

#Anna Komnene, who married the Caesar Nicephorus Bryennius.

#Maria Komnene, who married (1) Gregory Gabras and (2) Nicephorus Euphorbenos Katakalon.

#John II Komnenos, who succeeded as emperor.

#Andronikos Comnenus, sebastokratōr.

#Isaac Comnenus, sebastokratōr.

#Eudocia Komnene, who married Michael Iasites.

#Theodora Komnene, who married (1) Constantine Kourtikes and (2) Constantine Angelos. By him she was the grandmother of Emperors Isaac II Angelos and Alexios III Angelos.

#Manuel Komnenos.

#Zoe Komnene.

*--------------------

Alexios I Komnenos, or Comnenus (Greek: Αλέξιος Α' Κομνηνός) (1048 – August 15, 1118), Byzantine emperor (1081–1118), was the son of John Comnenus and Anna Dalassena and the nephew of Isaac I Comnenus (emperor 1057–1059). The military, financial and territorial recovery of the Byzantine Empire began in his reign.

Life

Alexius' father declined the throne on the abdication of Isaac, who was accordingly succeeded by four emperors of other families between 1059 and 1081. Under one of these emperors, Romanus IV Diogenes (1067–1071), he served with distinction against the Seljuk Turks. Under Michael VII Ducas Parapinaces (1071–1078) and Nicephorus III Botaneiates (1078–1081), he was also employed, along with his elder brother Isaac, against rebels in Asia Minor, Thrace and in Epirus.

Alexius' mother wielded great influence during his reign, and he is described by his daughter, the historian Anna Comnena, as running next to the imperial chariot that she drove. In 1074, the rebel mercenaries in Asia Minor were successfully subdued, and, in 1078, he was appointed commander of the field army in the West by Nicephorus III. In this capacity, Alexius defeated the rebellions of two successive governors of Dyrrhachium, Nicephorus Bryennius (whose son or grandson later married Alexius' daughter Anna) and Nicephorus Basilakes. Alexius was ordered to march against his brother-in-law Nicephorus Melissenus in Asia Minor but refused to fight his kinsman. This did not, however, lead to a demotion, as Alexius was needed to counter the expected Norman invasion led by Robert Guiscard near Dyrrhachium.

While the Byzantine troops were assembling for the expedition, Alexius was approached by the Ducas faction at court, who convinced him to join a conspiracy against Nicephorus III. Alexius was duly proclaimed emperor by his troops and marched on Constantinople. Bribing the western mercenaries guarding the city, the rebels entered Constantinople in triumph, meeting little resistance on April 1, 1081. Nicephorus III was forced to abdicate and retire to a monastery, and Patriarch Cosmas I crowned Alexius I emperor on April 4.

During this time, Alexius was rumored to be the lover of Empress Maria of Alania, the daughter of King Bagrat IV of Georgia, who had been successively married to Michael VII Ducas and his successor Nicephorus III Botaneiates, and was renowned for her beauty. Alexius arranged for Maria to stay on the palace grounds. It was also thought that Alexius may have been considering marrying the erstwhile empress. However, his mother consolidated the Ducas family connection by arranging the Emperor's marriage to Irene Ducaena, granddaughter of the Caesar John Ducas, the uncle of Michael VII, who would not have supported Alexius otherwise. As a measure intended to keep the support of the Ducae, Alexius restored Constantine Ducas, the young son of Michael VII and Maria, as co-emperor and a little later betrothed him to his own first-born daughter Anna, who moved into the Mangana Palace with her fiancé and his mother.

However, this situation changed drastically when Alexius' first son John II Comnenus was born in 1087: Anna's engagement to Constantine was dissolved, and she was moved to the main Palace to live with her mother and grandmother. Alexius became estranged from Maria, who was stripped of her imperial title and retired to a monastery, and Constantine Ducas was deprived of his status as co-emperor. Nevertheless, he remained in good relations with the imperial family and succumbed to his weak constitution soon afterwards.

Byzantine-Norman Wars

Alexius' long reign of nearly thirty-seven years was full of struggle. At the very outset, he had to meet the formidable attack of the Normans (led by Robert Guiscard and his son Bohemund), who took Dyrrhachium and Corfu, and laid siege to Larissa in Thessaly (see Battle of Dyrrhachium). Alexius suffered several defeats before being able to strike back with success. He enhanced this by bribing the German king Henry IV with 360,000 gold pieces to attack the Normans in Italy, which forced the Normans to concentrate on their defenses at home in 1083–1084. He also secured the alliance of Henry, Count of Monte Sant'Angelo, who controlled the Gargano Peninsula and dated his charters by Alexius' reign. Henry's allegiance was to be the last example of Byzantine political control on peninsular Italy. The Norman danger ended for the time being with Robert Guiscard's death in 1085, and the Byzantines recovered most of their losses.

Alexius had next to deal with disturbances in Thrace, where the heretical sects of the Bogomils and the Paulicians revolted and made common cause with the Pechenegs from beyond the Danube. Paulician soldiers in imperial service likewise deserted during Alexius' battles with the Normans. As soon as the Norman threat had passed, Alexius set out to punish the rebels and deserters, confiscating their lands. This led to a further revolt near Philippopolis, and the commander of the field army in the west, Gregory Pakourianos, was defeated and killed in the ensuing battle. In 1087 the Pechenegs raided into Thrace and Alexius crossed into Moesia to retaliate but failed to take Dorostolon (Silistra). During his retreat, the emperor was surrounded and worn down by the Pechenegs, who forced him to sign a truce and pay protection money. In 1090 the Pechenegs invaded Thrace again, while the brother-in-law of the Sultan of Rum launched a fleet and attempted to arrange a joing siege of Constantinople with the Pechenegs. Alexius overcame this crisis by entering into an alliance with a horde of 40,000 Cumans, with whose help he crushed the Pechenegs at Levounion in Thrace on April 29, 1091.

This put an end to the Pecheneg threat, but in 1094 the Cumans began to raid the imperial territories in the Balkans. Led by a pretender claiming to be Constantine Diogenes, a long-dead son of the Emperor Romanos IV, the Cumans crossed the mountains and raided into eastern Thrace until their leader was eliminated at Adrianople. With the Balkans more or less pacified, Alexius could now turn his attention to Asia Minor, which had been almost completely overrun by the Seljuk Turks.

Byzantine-Seljuk Wars

As early as 1090, Alexius had taken reconciliatory measures towards the Papacy, with the intention of seeking western support against the Seljuks. In 1095 his ambassadors appeared before Pope Urban II at the Council of Piacenza. The help which he wanted from the West was simply mercenary forces and not the immense hosts which arrived, to his consternation and embarrassment, after the pope preached the First Crusade at the Council of Clermont later that same year. Not quite ready to supply this number of people as they traversed his territories, the emperor saw his Balkan possessions subjected to further pillage at the hands of his own allies. Alexius dealt with the first disorganized group of crusaders, led by the preacher Peter the Hermit, by sending them on to Asia Minor, where they were massacred by the Turks in 1096.

The second and much more formidable host of crusaders gradually made its way to Constantinople, led in sections by Godfrey of Bouillon, Bohemund of Taranto, Raymond IV of Toulouse and other important members of the western nobility. Alexius used the opportunity of meeting the crusader leaders separately as they arrived and extracting from them oaths of homage and the promise to turn over conquered lands to the Byzantine Empire. Transferring each contingent into Asia, Alexius promised to supply them with provisions in return for their oaths of homage. The crusade was a notable success for Byzantium, as Alexius now recovered for the Byzantine Empire a number of important cities and islands. The crusader siege of Nicaea forced the city to surrender to the emperor in 1097, and the subsequent crusader victory at Dorylaion allowed the Byzantine forces to recover much of western Asia Minor. Here Byzantine rule was reestablished in Chios, Rhodes, Smyrna, Ephesus, Sardis, and Philadelphia in 1097–1099. This success is ascribed by his daughter Anna to his policy and diplomacy, but by the Latin historians of the crusade to his treachery and falseness. In 1099, a Byzantine fleet of 10 ships were sent to assist the Crusaders in capturing Laodicea and other coastal towns as far as Tripoli. The crusaders believed their oaths were made invalid when the Byzantine contingent under Tatikios failed to help them during the siege of Antioch; Bohemund, who had set himself up as Prince of Antioch, briefly went to war with Alexius in the Balkans, but was blockaded by the Byzantine forces and agreed to become Alexius' vassal by the Treaty of Devol in 1108.

Personal life

During the last twenty years of his life Alexius lost much of his popularity. The years were marked by persecution of the followers of the Paulician and Bogomil heresies—one of his last acts was to publicly burn on the stake Basil, a Bogomil leader, with whom he had engaged in a theological dispute. In spite of the success of the crusade, Alexius also had to repel numerous attempts on his territory by the Seljuks in 1110–1117.

Alexius was for many years under the strong influence of an eminence grise, his mother Anna Dalassena, a wise and immensely able politician whom, in a uniquely irregular fashion, he had crowned as Augusta instead of the rightful claimant to the title, his wife Irene Ducaena. Dalassena was the effective administrator of the Empire during Alexius' long absences in military campaigns: she was constantly at odds with her daughter-in-law and had assumed total responsibility for the upbringing and education of her granddaughter Anna Comnena.

Succession

Alexius' last years were also troubled by anxieties over the succession. Although he had crowned his son John II Comnenus co-emperor at the age of five in 1092, John's mother Irene Doukaina wished to alter the succession in favor of her daughter Anna and Anna's husband, Nicephorus Bryennius. Bryennios had been made kaisar (Caesar) and received the newly-created title of panhypersebastos ("honoured above all"), and remained loyal to both Alexius and John. Nevertheless, the intrigues of Irene and Anna disturbed even Alexius' dying hours.

Legacy

Alexius I had stabilized the Byzantine Empire and overcome a dangerous crisis, inaugurating a century of imperial prosperity and success. He had also profoundly altered the nature of the Byzantine government. By seeking close alliances with powerful noble families, Alexius put an end to the tradition of imperial exclusivity and coopted most of the nobility into his extended family and, through it, his government. This measure, which was intended to diminish opposition, was paralleled by the introduction of new courtly dignities, like that of panhypersebastos given to Nicephorus Bryennius, or that of sebastokrator given to the emperor's brother Isaac Comnenus. Although this policy met with initial success, it gradually undermined the relative effectiveness of imperial bureaucracy by placing family connections over merit. Alexius' policy of integration of the nobility bore the fruit of continuity: every Byzantine emperor who reigned after Alexius I Comnenus was related to him by either descent or marriage.

Family

By his marriage with Irene Ducaena, Alexius I had the following children:

Anna Komnene, who married the Caesar Nicephorus Bryennius.

Maria Komnene, who married (1) Gregory Gabras and (2) Nicephorus Euphorbenos Katakalon.

John II Komnenos, who succeeded as emperor.

Andronikos Comnenus, sebastokratōr.

Isaac Comnenus, sebastokratōr.

Eudocia Komnene, who married Michael Iasites.

Theodora Komnene, who married (1) Constantine Kourtikes and (2) Constantine Angelos. By him she was the grandmother of Emperors Isaac II Angelos and Alexios III Angelos.

Manuel Komnenos.

Zoe Komnene.

Alexios I Komnenos or Alexius I Comnenus (Greek: Αλέξιος Α' Κομνηνός, Alexios I Komnēnos; Latin: ALEXIVS I COMNENVS; 1048 – August 15, 1118), Byzantine emperor (1081–1118), was the son of John Komnenos and Anna Dalassena and the nephew of Isaac I Komnenos (emperor 1057–1059). The military, financial and territorial recovery of the Byzantine Empire known as Komnenian restoration began in his reign.

Life

Alexios' father declined the throne on the abdication of Isaac, who was accordingly succeeded by four emperors of other families between 1059 and 1081. Under one of these emperors, Romanos IV Diogenes (1067–1071), he served with distinction against the Seljuk Turks. Under Michael VII Doukas Parapinakes (1071–1078) and Nikephoros III Botaneiates (1078–1081) he was also employed, along with his elder brother Isaac, against rebels in Asia Minor, Thrace and in Epirus.

Alexios' mother wielded great influence during his reign and he is described by his daughter, the historian Anna Comnena, as running next to the imperial chariot that she drove. In 1074 the rebel mercenaries in Asia Minor were successfully subdued and in 1078 he was appointed commander of the field army in the West by Nikephoros III. In this capacity Alexios defeated the rebellions of two successive governors of Dyrrhachium, Nicephorus Bryennios (whose son or grandson later married Alexios' daughter Anna), and Nicephorus Basilakes. Alexios was ordered to march against his brother-in-law Nikephoros Melissenos in Asia Minor, but refused to fight his kinsman. This did not, however, lead to a demotion, as Alexios was needed to counter the expected Norman invasion led by Robert Guiscard near Dyrrhachium.

While the Byzantine troops were assembling for the expedition, Alexios was approached by the Doukas faction at court, who convinced him to join a conspiracy against Nikephoros III. Alexios was duly proclaimed emperor by his troops and marched on Constantinople. Bribing the western mercenaries guarding the city, the rebels entered Constantinople in triumph, meeting little resistance on April 1, 1081. Nikephoros III was forced to abdicate and retire to a monastery, and Patriarch Kosmas I crowned Alexios I emperor on April 4.

During this time, Alexios was rumored to be the lover of Empress Maria of Alania, the daughter of King Bagrat IV of Georgia who had been successively married to Michael VII Doukas and his successor Nikephoros III Botaneiates, and was renowned for her beauty. Alexios arranged for Maria to stay on the palace grounds. It was also thought that Alexios may have been considering marrying the erstwhile empress. However his mother consolidated the Doukas family connection by arranging the Emperor's marriage to Irene Doukaina, granddaughter of the Caesar John Doukas, the uncle of Michael VII, who would not have supported Alexios otherwise. As a measure intended to keep the support of the Doukai, Alexios restored Constantine Doukas, the young son of Michael VII and Maria, as co-emperor and a little later betrothed him to his own first-born daughter Anna, who moved into the Mangana Palace with her fiance and his mother.

However, this situation changed drastically when Alexios' first son John II Komnenos was born in 1087: Anna's engagement to Constantine was dissolved and she was moved to the main Palace to live with her mother and grandmother. Alexios became estranged from Maria, who was stripped of her imperial title and retired to a monastery, and Constantine Doukas was deprived of his status as co-emperor. Nevertheless he remained in good relations with the imperial family and succumbed to his weak constitution soon afterwards.

Byzantine-Norman Wars

Alexios' long reign of nearly 37 years was full of struggle. At the very outset he had to meet the formidable attack of the Normans (led by Robert Guiscard and his son Bohemund), who took Dyrrhachium and Corfu, and laid siege to Larissa in Thessaly (see Battle of Dyrrhachium). Alexios suffered several defeats before being able to strike back with success. He enhanced this by bribing the German king Henry IV with 360,000 gold pieces to attack the Normans in Italy, which forced the Normans to concentrate on their defenses at home in 1083–1084. He also secured the alliance of Henry, Count of Monte Sant'Angelo, who controlled the Peninsula del Gargano and dated his charters by Alexius' reign. Henry's allegiance was to be the last example of Greek political control on peninsular Italy. The Norman danger ended for the time being with Robert Guiscard's death in 1085, and the Byzantines recovered most of their losses.

Alexios had next to deal with disturbances in Thrace, where the heretical sects of the Bogomils and the Paulicians revolted and made common cause with the Pechenegs from beyond the Danube. Paulician soldiers in imperial service likewise deserted during Alexios' battles with the Normans. As soon as the Norman threat had passed, Alexios set out to punish the rebels and deserters, confiscating their lands. This led to a further revolt near Philippopolis (Plovdiv), and the commander of the field army in the west, Gregory Pakourianos, was defeated and killed in the ensuing battle. In 1087 the Pechenegs raided into Thrace and Alexios crossed into Moesia to retaliate but failed to take Dorostolon (Silistra). During his retreat, the emperor was surrounded and worn down by the Pechenegs, who forced him to sign a truce and pay protection money. In 1090 the Pechenegs invaded Thrace again, while the brother-in-law of the Sultan of Rum launched a fleet and attempted to arrange a joing siege of Constantinople with the Pechenegs. Alexios overcame this crisis by entering into an alliance with a horde of 40,000 Cumans, with whose help he crushed the Pechenegs at Levounion in Thrace on April 29, 1091.

This put an end to the Pecheneg threat, but in 1094 the Cumans began to raid the imperial territories in the Balkans. Led by a pretender claiming to be Constantine Diogenes, a long-dead son of the Emperor Romanos IV, the Cumans crossed the mountains and raided into eastern Thrace until their leader was eliminated at Adrianople. With the Balkans more or less pacified, Alexios could now turn his attention to Asia Minor, which had been almost completely overrun by the Seljuk Turks.

[edit]Byzantine-Seljuk Wars

As early as 1090, Alexios had taken reconciliatory measures towards the Papacy, with the intention of seeking western support against the Seljuks. In 1095 his ambassadors appeared before Pope Urban II at the Council of Piacenza. The help which he wanted from the West was simply mercenary forces and not the immense hosts which arrived, to his consternation and embarrassment, after the pope preached the First Crusade at the Council of Clermont later that same year. Not quite ready to supply this number of people as they traversed his territories, the emperor saw his Balkan possessions subjected to further pillage at the hands of his own allies. Alexios dealt with the first disorganized group of crusaders, led by the preacher Peter the Hermit, by sending them on to Asia Minor, where they were massacred by the Turks in 1096.

The second and much more formidable host of crusaders gradually made its way to Constantinople, led in sections by Godfrey of Bouillon, Bohemund of Taranto, Raymond IV of Toulouse and other important members of the western nobility. Alexios used the opportunity of meeting the crusader leaders separately as they arrived and extracting from them oaths of homage and the promise to turn over conquered lands to the Byzantine Empire. Transferring each contingent into Asia, Alexios promised to supply them with provisions in return for their oaths of homage. The crusade was a notable success for Byzantium, as Alexios now recovered for the Byzantine Empire a number of important cities and islands. The crusader siege of Nicaea forced the city to surrender to the emperor in 1097, and the subsequent crusader victory at Dorylaion allowed the Byzantine forces to recover much of western Asia Minor. Here Byzantine rule was reestablished in Chios, Rhodes, Smyrna, Ephesus, Philadelphia, and Sardis in 1097–1099. This success is ascribed by his daughter Anna to his policy and diplomacy, but by the Latin historians of the crusade to his treachery and falseness. In 1099, a Byzantine fleet of 10 ships were sent to assist the Crusaders in capturing Laodicea and other coastal towns as far as Tripoli. The crusaders believed their oaths were made invalid when the Byzantine contingent under Tatikios failed to help them during the siege of Antioch; Bohemund, who had set himself up as Prince of Antioch, briefly went to war with Alexios in the Balkans, but was blockaded by the Byzantine forces and agreed to become Alexios' vassal by the Treaty of Devol in 1108.

[edit]Personal life

During the last twenty years of his life Alexios lost much of his popularity. The years were marked by persecution of the followers of the Paulician and Bogomil heresies—one of his last acts was to publicly burn on the stake Basil, a Bogomil leader, with whom he had engaged in a theological dispute. In spite of the success of the crusade, Alexios also had to repel numerous attempts on his territory by the Seljuks in 1110–1117.

Alexios was for many years under the strong influence of an eminence grise, his mother Anna Dalassene, a wise and immensely able politician whom, in a uniquely irregular fashion, he had crowned as Augusta instead of the rightful claimant to the title, his wife Irene Doukaina. Dalassena was the effective administrator of the Empire during Alexius' long absences in military campaigns: she was constantly at odds with her daughter-in-law and had assumed total responsibility for the upbringing and education of her granddaughter Anna Komnene.

[edit]Succession