Généalogie Kuipers » Franz Liszt (1811-1886)

Données personnelles Franz Liszt

- Il est né le 22 octobre 1811 dans Oberpullendorf, Burgenland, Austria.

Voorheen: Doborján, , Hungary

- Professions:

- Pianist.

- Composer.

- Saksische Hofkapelmeister.

- Il est décédé le 31 juillet 1886 dans Bayreuth, Bayern, Germany, il avait 74 ans.

- Un enfant de Adam Liszt et Anna Maria Lager

- Cette information a été mise à jour pour la dernière fois le 4 août 2009.

Famille de Franz Liszt

Il est marié avec Marie Catherine Sophie de Flavigny.

Ils se sont mariés environ 1835.

Zie ES NF Band XIV Tafel 14

geen wettelijk huwelijk, maar een buitenechtelijke verbintenis!

RFN 8198

Enfant(s):

- Daniel Liszt 1839-1859

Notes par Franz Liszt

(Research):Franz Liszt (Hungarian: Liszt Ferenc; pronounced [?l?st ?f?r?nts]) (October 22, 1811 July 31, 1886) was a Hungarian composer, teacher and virtuoso of the 19th century. He was a renowned performer throughout Europe, noted especially for his showmanship and great skill with the piano. To this day, he is considered by some to have been the greatest pianist in history.[1] He used both his technique and his concert personality not only for personal effect but also, through his transcriptions, to spread knowledge of other composers' music.[2]

As a composer, Liszt was one of the most prominent representatives of the "Neudeutsche Schule" ("New German School"). He left behind a huge oeuvre, including works from nearly all musical genres. In his compositions he developed new methods, both imaginative and technical, which influenced his forward-looking contemporaries and anticipated some 20th-century ideas and trends. These included his inventing the symphonic poem for orchestra, evolving the concept of thematic transformation as part of his experiments in musical form and making radical departures in harmony.[3]

Early life

Franz Liszt was born on October 22, 1811, in the village of Raiding (Hungarian: Doborján) in the Kingdom of Hungary, then part of the Habsburg Empire (and today also part of Austria), in the comitat Oedenburg (Hungarian: Sopron). In the vast majority of Liszt literature he is regarded as either Hungarian or German. Every attempt to describe Liszt's development during his childhood and early youth has met with the difficulties of terribly sparse information. It had been Adam Liszt's own dream to become a musician. He played piano, violin, violoncello, and guitar, was in the services of Prince Nikolaus II Esterházy and knew Haydn, Hummel and Beethoven personally.

At age six, Franz began listening attentively to his father's piano playing as well as to show an interest in both sacred and gypsy music. Adam recognized his son's musical talent early. He began teaching Franz the piano at age seven and Franz began composing in an elementary manner when he was eight. He may have also first played in public at Baden at age eight; he definitely appeared in concerts at Sopron and Poszony in October and November 1820. After these concerts, a group of Hungarian magnates offered to finance Franz's musical education abroad.[4]

In Vienna, Liszt received piano lessons from Carl Czerny, who in his own youth had been a student of Ludwig van Beethoven. He also received lessons in composition by Antonio Salieri, who was then music director of the Viennese court. His public debut in Vienna on December 1, 1822, at a concert at the "Landständischer Saal," was a great success. He was greeted in Austrian and Hungarian aristocratic circles and also met Beethoven and Franz Schubert. At a second concert on April 13, 1823, Beethoven was reputed to have kissed Liszt on the forehead. While Liszt himself told this story later in life, this incident may have occurred on a different occasion. Regardless, Liszt regarded it as a form of artistic christening. He was asked by the publisher Diabeli to contribute a variation on a waltz of the publisher's own invention the same waltz to which Beethoven would write his noted set of 33 variations.[4]

In spring 1823, when the one year's leave of absence came to an end, Adam Liszt asked Prince Esterházy in vain for two more years. Adam Liszt therefore took his leave of the Prince's services. At the end of April 1823, the family for the last time returned to Hungary. At end of May 1823, the family went to Vienna again.

[edit] Child prodigy

On September 20, 1823, the Liszt family left Vienna for Paris. To support himself and his parents, Liszt gave concerts in Munich, Augsburg, Stuttgart and Strasbourg. In Paris, the director of the Conservatoire, Cherubini, refused Liszt admission on the grounds that he was a foreigner. Liszt studied theory with Anton Reicha and composition with Ferdinando Paar.[4]

Liszt was a success in Paris society, playing at many fashionable concerts; his first, on March 7, 1824, was a sensation. In the spring he visited England for the first time. He played at the Argyle Room on June 21 and Drury Lane on June 29. He toured the French provinces the following spring then returned to England, playing in London, in Manchester and before King George IV. He had also been actively composing. While nearly all of those works are lost, some piano works of 1824 were published. These pieces were written in the common style of the contemporary brilliant Viennese school. He had taken works of his former master Czerny as a model, which Liszt's later virtuoso rivals Sigismond Thalberg and Theodor Döhler would also emulate. However, in 1826 he composed the Etude in douze exercises, the original version of the Transcendental Studies. This marked the beginning of Liszt's career as a serious composer.[4]

In 1826 Liszt again toured the French provinces as well as Switzerland that winter. This was followed by a third tour of England. However, the constant touring was beginning to affect the boy's health, while at the same time he expressed a desire to become a priest. [4] In summer 1827, Liszt fell ill.[5] Adam Liszt went with his son to Boulogne-sur-Mer, a spa town on the English Channel. While Liszt himself was recovering, his father Adam fell ill with typhus. On August 28, 1827, Adam Liszt died.

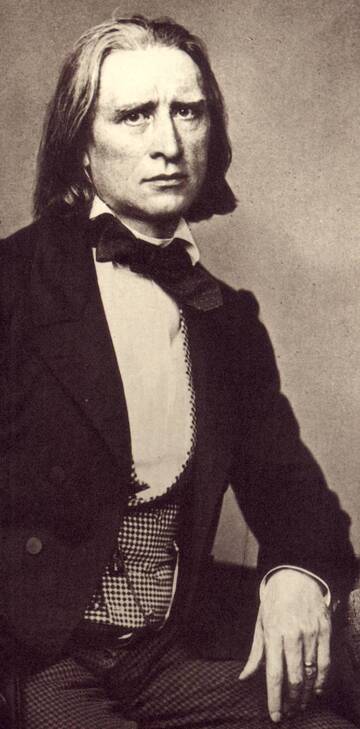

Liszt, in a lithograph by Achille Devéria, 1832.

Liszt, in a lithograph by Achille Devéria, 1832.

[edit] Adolescence in Paris

After his father's death Liszt returned to Paris; for the next five years he was to live with his mother in a small apartment. He gave up touring. To earn money, Liszt gave lessons in piano playing and composition, often from early morning until late at night. His students were scattered across the city and he often had to cross long distances. Because of this, Liszt kept uncertain hours and also took up smoking and drinking all habits he would continue throughout his life.[6][7]

The following year he fell in love with one of his pupils, Caroline de Saint-Cricq, the daughter of Charles X's minister of commerce. However, her father insisted that the affair be broken off. Liszt again fell ill (there was even an obituary notice of him printed in a Paris newspaper), and he underwent a long period of religious doubts and pessimism. He again stated a wish to join the Church but was dissuaded this time by his mother. He had many discussions with the Abbe de Lamennais, who acted as his spiritual father, and also with Chrétien Urhan, a German-born violinist who introduced him to the Saint-Simonists.[6] Urhan also wrote music that was anti-classical and highly subjective, with titles such as Elle et moi, La Salvation angélique and Les Regrets, and may have whetted the young Liszt's taste for musical romanticism. Equally important for Liszt was Urhan's earnest championship of Schubert, which may have stimulated his own lifelong devotion to that composer's music.[8]

During this period Liszt read widely to overcome his lack of a general education, and he soon came into contact with many of the leading authors and artists of his day, including Victor Hugo, Lamartine and Heine. He composed practically nothing in these years. Nevertheless, the July Revolution of 1830 inspired him to sketch a Revolutionary Symphony based on the events of the "three glorious days," and he took a greater interest in events surrounding him. He met Hector Berlioz on December 4, 1830, the day before the premiere of the Symphonie fantastique. Berlioz's music made a strong impression on Liszt, especially later when he was writing for orchestra. He also inherited from Berlioz the diabolic quality of many of his works.[6]

Niccolò Paganini. His playing inspired Liszt to become as great a virtuoso.

Niccolò Paganini. His playing inspired Liszt to become as great a virtuoso.

After attending an April 20, 1832 charity concert, for the victims of a Parisian cholera epidemic, by Niccolò Paganini,[9] Liszt became determined to become as great a virtuoso on the piano as Paganini was on the violin. Nor was Liszt alone in developing his technique. Paris in the 1830s had become the nexus for pianistic activities, with dozens of steel-fingered pianists dedicated to perfection at the keyboard. Some, such as Sigismond Thalberg and Alexander Dreyschook, focused on specific aspects of technique. While it was called the "flying trapeze" school of piano playing, this generation also solved some of the most intractable problems of piano technique, raising the general level of performance to previously unimagined heights. Liszt's strength and ability to stand out in this company was in mastering all the aspects of piano technique cultivated singly and assiduously by his rivals.[10]

In 1833 he made transcriptions of several works by Berlioz, including the Symphonie fantastique his chief motive in doing so, especially with the Symphonie, was to help the poverty-stricken Berlioz, whose symphony remained unknown and unpublished. He bore the expense of publishing the transcription himself and played it many times to help popularize the original score.[11] He was also forming a friendship with the third composer who would influence him, Frederic Chopin; under his influence Liszt's poetic and romantic side began to develop.[6]

[edit] With Countess Marie d'Agoult

In 1833, Liszt began his relationship with the Countess Marie d'Agoult. In addition to this, at the end of April 1834 he made the acquaintance of Felicité de Lamennais. Under the influence of both, Liszt's creative output exploded. In 1834 Liszt debuted as a mature and original composer with his Harmonies poetiques et religieuses and the set of three Apparitions. These were all poetic works which contrasted strongly with the fantasies he had written earlier.[6]

In 1835 the countess left her husband and family to join Liszt in Geneva; their daughter Blandine was born there on December 18. Liszt taught at the newly-founded Geneva Conservatory, wrote a manual of piano technique (later lost)[12] and contributed essays for the Paris Revue et gazette musicale. In these essays, he argued for the raising of the artist from the status of a servant to a respected member of the community.[6]

For the next four years Liszt and the countess lived together, mainly in Switzerland and Italy with occasional visits to Paris. During one of these visits in the winter of 1936-7, Liszt participated in a Berlioz concert, gave chamber music concerts and, on March 31, played at Princess Belgiojoso's home in a celebrated pianistic duel with Thalberg. Thalberg's reputation was beginning to eclipse Liszt's, but Liszt matched him handily in playing.[13] Critic Jules Janin wrote a detailed description of the duel, commenting,

Never was Liszt more controlled, more thoughtful, more energetic, more passionate; never has Thalberg played with greater verve and tenderness. Each of them prudently stayed within his harmonic domain, but each used every one of his resources. It was an admirable joust. The most profound silence fell over that noble arena. And finally Liszt and Thalberg were both proclaimed victors by this glittering and intelligent assembly. It is clear that such a contest could only take place in the presence of such an Areopagus. Thus two victors and no vanquished; it is fitting to say with the poet ET AD HUC SUB JUDICE LIS EST.[14]

When the princess herself was asked to summarize the event, she gave the diplomatic aphorism, "Thalberg is the first pianist in the world Liszt is the only one."[14]

Liszt also composed the Album d'un voyager; these were lyrical evocations of Swiss scenes which he later reworked for his first book of Années de Pèlerinage. He wrote the second book of Années in 1837 while in Italy with the countess; he also composed the first version of the Paganini Studies and the 12 grandes etudes, a greatly revised and expanded and revised version of the Etude in douze exercises. On Christmas day their second daughter, Cosima, was born at Bellagio, on Lake Como. In 1838 Liszt gave concerts in Vienna and various Italian cities. he also began what would become a long series of Schubert transcriptions as well as the initial version of the Totentanz.[6]

On May 9, 1839 Liszt and the countess's only son, Daniel, was born, but that autumn relations between them became strained. Liszt heard that plans for a Beethoven monument in Bonn were in danger of collapse for lack of funds and pledged his support. Doing so meant returning to the life of a touring virtuoso. The countess returned to Paris with the children while Liszt gave six concerts in Vienna then toured Hungary.[6]

[edit] Touring virtuoso

For the next eight years Liszt continued to tour Europe; spending summer holidays with the countess and their children on the island of Nonnenwerth on the Rhine until 1844, when the couple finally separated and Liszt took the children to Paris to see about their education. This was Liszt's most brilliant period as a concert pianist. Honors were showered on him and he was adulated everywhere he went.[6] Since Liszt often appeared three or four times a week in concert, it could be safe to assume that he appeared in public well over a thousand times during this eight-year period. Moreover, his great fame as a pianist, which he would continue to enjoy long after he had officially retired from the concert stage, was based mainly on his accomplishments during this time.[15]

After 1842 "Lisztomania" swept across Europe. The reception Liszt enjoyed as a result can only be described as hysterical. Women fought over his silk handkerchiefs and velvet gloves, which they ripped to shreads as souvenirs. More soberly-minded musicians such as Schumann, Chopin and Mendelsssohn were appalled by these displays of hero worship, eventually despising Liszt because of them. The emotionally charged atmosphere of his recitals made them seem more like séances than serious musical events. Helping fuel this atmosphere was the artist's mesmeric personality and stage presence. Many witnesses later testified that Liszt's plauing raised the mood of audiences to a level of mystical ecstasy.[16]

Adding to his reputation was the fact that Liszt gave away much of his proceeds to charity and humanitarian causes. While his work for the Beethoven monument and the Hungarian National School of Music are well known, he also gave generously to the building fund of Cologne Cathedral, the establishment of a Gymnasium at Dortmund and the construction of the Leopold Church in Pest. There were also private donations to hospitals, schools and charitable organizations such as the Leipzig Musicians Pension Fund. When he found out about the Great Fire of Hamburg, which raged three weeks during May 1842 and immolated much of the city, he gave concerts in aid of the thousands of homeless there.[17]

[edit] Liszt in Weimar

A statue of Liszt

A statue of Liszt

In February 1847, Liszt played in Kiev. There he met the Princess Carolyne zu Sayn-Wittgenstein, who would dominate most of the rest of his life. She persuaded him to concentrate on composition, which meant giving up his career as a traveling virtuoso. After a tour of the Balkans, Turkey and Russia that summer, Liszt gave his final concert for pay at Elisavetgrad in September. He spent the winter with the princess at her estate in Worononce.[18] By retiring from concertizing at age 35, while still at the height of his powers, Liszt succeeded in keeping the legend of his playing untarnished.[19]

The following year, Liszt took up a long-standing invitation of Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna of Russia to settle at Weimar, where he had been appointed Kapellmeister Extraordinaire in 1842, remaining there until 1861. During this period he acted as conductor at court concerts and on special occasions at the theatre. He gave lessons to a number of pianists, including the great virtuoso Hans von Bülow, who married Liszt's daughter Cosima in 1857 (before she was married to Wagner). He also wrote articles championing Berlioz and Wagner. Finally, Liszt had ample time to compose and during the next 12 years revised or produced those orchestral and choral pieces upon which his reputation as a composer mainly rests. His efforts on behalf of Wagner, who was then an exile in Switzerland, culminated in the first performance of Lohengrin in 1850.

Princess Carolyne lived with Liszt during his years in Weimar. She eventually wished to marry Liszt, but since she had been previously married and her husband, Russian military officer Prince Nikolaus zu Sayn-Wittgenstein-Ludwigsburg (1812-1864), was still alive, she had to convince the Roman Catholic authorities that her marriage to him had been invalid. After huge efforts and a monstrously intricate process, she was temporarily successful (September 1860). It was planned that the couple would marry in Rome, on October 22, 1861, Liszt's 50th birthday. Liszt having arrived in Rome on October 21, 1861, the Princess nevertheless declined, by the late evening, to marry him. It appears that both her husband and the Czar of Russia had managed to quash permission for the marriage at the Vatican. The Russian government also impounded her several estates in the Polish Ukraine, which made her later marriage to anybody unfeasible.

[edit] Liszt in Rome

Liszt, photo by Franz Hanfstaengl, June 1867.

Liszt, photo by Franz Hanfstaengl, June 1867.

The 1860s were a period of severe catastrophes of Liszt's private life. After he had on December 13, 1859, already lost his son Daniel, on September 11, 1862, also his daughter Blandine died. In letters to friends Liszt afterwards announced, he would retreat to a solitary living. He found it at the monastery Madonna del Rosario, just outside Rome, where on June 20, 1863, he took up quarters in a small, Spartan apartment. He had on June 23, 1857, already joined a Franciscan order.[20] On April 25, 1865, he received from Gustav Hohenlohe the tonsure and a first one of the minor orders of the Catholic Church. Three further minor orders followed on July 30, 1865. Until then, Liszt was Porter, Lector, Exorcist, and Acolyte. While Princess Wittgenstein tried to persuade him to proceed in order to become priest, he did not follow her. In his later years he explained, he had wanted to preserve a rest of his freedom.[21]

At some occasions, Liszt took part in Rome's musical life. On March 26, 1863, at a concert at the Palazzo Altieri, he directed a program of sacral music. The "Seligkeiten" of his "Christus-Oratorio" and his "Cantico del Sol di Francesco d'Assisi", as well as Haydn's "Die Schöpfung" and works by J. S. Bach, Beethoven, Jornelli, Mendelssohn and Palestrina were performed. On January 4, 1866, Liszt directed the "Stabat mater" of his "Christus-Oratorio", and on February 26, 1866, his "Dante-Symphony". There were several further occasions of similar kind, but in comparison with the duration of Liszt's stay in Rome, they were exceptions. Bódog Pichler, who visited Liszt in 1864 and asked him for his future plans, had the impression that Rome's musical life was not satisfying for Liszt.[22]

[edit] Threefold life

Liszt was invited back to Weimar in 1869 to give master classes in piano playing. Two years later he was asked to do the same in Budapest at the Hungarian Music Academy. From then until the end of his life he made regular journeys between Rome, Weimar and Budapest, continuing what he called his "vie trifurquée" or threefold existence. It is estimated that Liszt travelled at least 4000 miles a year during this period in his life an exceptional figure given his advancing age and the rigors of road and rail in the 1870's.[23]

[edit] Last years

Liszt at the piano, an engraving based on a photograph by Louis Held, Weimar, 1885.

Liszt at the piano, an engraving based on a photograph by Louis Held, Weimar, 1885.

On July 2, 1881, Liszt fell down the stairs of the Hofgärtnerei in Weimar. Though friends and colleagues had noted swelling in Liszt's feet and legs when he had arrived in Weimar the previous month, Liszt had up to this point been in reasonably good health, and his body retained the slimness and suppleness of earlier years. The accident, which immobilized him for eight weeks, changed this. A number of ailments manifested dropsy, asthma, insomnia, a cataract of the left eye and chronic heart disease. The last mentioned would eventually contribute to Liszt's death. He would become increasingly plagued with feelings of desolation, despair and death feelings he would continue to express nakedly in his works from this period. As he told Lina Ramann, "I carry a deep sadness of the heart which must now and then break out in sound."[24]

He died in Bayreuth on July 31, 1886, officially as a result of pneumonia which he may have contracted during the Bayreuth Festival hosted by his daughter Cosima. At first, he was surrounded by some of his more adoring pupils, including Arthur Friedheim, Siloti and Bernhard Stavenhagen, but they were denied access to his room by Cosima shortly before his death at 11:30 p.m. He is buried in the Bayreuth cemetery. Questions have been posed as to whether medical malpractice played a direct part in Liszt's demise. At 11:30 Liszt was given two injections in the area of the heart. Some sources have claimed these were injections of morphine. Others have claimed the injections were of camphor, shallow injections of which, followed by massage, would warm the body. An accidental injection of camphor into the heart itself would result in a swift infarction and death. This series of events is exactly what Lina Schmalhaussen describes in the eyewitness account in her private diary, the most detailed source regarding Liszt's final illness.[25]

componist en pianist, Saksische Hofkapelmeister

Barre chronologique Franz Liszt

Cette fonctionnalité n'est disponible que pour les navigateurs qui supportent Javascript.

Cliquez sur le nom pour plus d'information.

Symboles utilisés:  grand-parents

grand-parents

parents

parents

frères/soeurs

frères/soeurs

enfants

enfants

grand-parents

grand-parents

parents

parents

frères/soeurs

frères/soeurs

enfants

enfants

Ancêtres (et descendants) de Franz Liszt

Franz Liszt  | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

± 1835 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Marie Catherine Sophie de Flavigny | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Les données affichées n'ont aucune source.

Des liens dans d'autres publications

On rencontre cette personne aussi dans la publication:Événements historiques

Jour de naissance 22 octobre 1811

- La température le 22 octobre 1811 était d'environ 13,0 °C. Le vent venait principalement de l'/du sud-sud-est. Caractérisation du temps: helder. Source: KNMI

- Cette page est uniquement disponible en néerlandais.De Republiek der Verenigde Nederlanden werd in 1794-1795 door de Fransen veroverd onder leiding van bevelhebber Charles Pichegru (geholpen door de Nederlander Herman Willem Daendels); de verovering werd vergemakkelijkt door het dichtvriezen van de Waterlinie; Willem V moest op 18 januari 1795 uitwijken naar Engeland (en van daaruit in 1801 naar Duitsland); de patriotten namen de macht over van de aristocratische regenten en proclameerden de Bataafsche Republiek; op 16 mei 1795 werd het Haags Verdrag gesloten, waarmee ons land een vazalstaat werd van Frankrijk; in 3.1796 kwam er een Nationale Vergadering; in 1798 pleegde Daendels een staatsgreep, die de unitarissen aan de macht bracht; er kwam een nieuwe grondwet, die een Vertegenwoordigend Lichaam (met een Eerste en Tweede Kamer) instelde en als regering een Directoire; in 1799 sloeg Daendels bij Castricum een Brits-Russische invasie af; in 1801 kwam er een nieuwe grondwet; bij de Vrede van Amiens (1802) kreeg ons land van Engeland zijn koloniën terug (behalve Ceylon); na de grondwetswijziging van 1805 kwam er een raadpensionaris als eenhoofdig gezag, namelijk Rutger Jan Schimmelpenninck (van 31 oktober 1761 tot 25 maart 1825).

- En l'an 1811: Source: Wikipedia

- 10 février » l'armée impériale russe rentre dans Belgrade en soutien au Premier soulèvement serbe dans le cadre de la Guerre russo-turque de 1806-1812.

- 18 mai » en Uruguay, bataille de Las Piedras.

- 5 juillet » déclaration d'indépendance du Venezuela.

- 25 octobre » bataille de Sagonte. Victoire des troupes de Suchet sur les Espagnols.

- 7 novembre » bataille de Tippecanoe.

- 2 décembre » le général chilien José Miguel Carrera dissout le Congrès(es) et instaure la dictature.

Jour du décès 31 juillet 1886

- La température le 31 juillet 1886 était d'environ 17,9 °C. Il y avait 1 mm de précipitation. La pression du vent était de 10 kgf/m2 et provenait en majeure partie du ouest-sud-ouest. La pression atmosphérique était de 75 cm de mercure. Le taux d'humidité relative était de 92%. Source: KNMI

- Du 23 avril 1884 au 21 avril 1888 il y avait aux Pays-Bas le cabinet Heemskerk avec comme premier ministre Mr. J. Heemskerk Azn. (conservatief).

- En l'an 1886: Source: Wikipedia

- La population des Pays-Bas était d'environ 4,5 millions d'habitants.

- 11 janvier » à New York, première partie du premier championnat du monde d’échecs officiel.

- 5 mars » l'anarchiste Charles Gallo accomplit un acte de propagande par le fait, en lançant une bouteille d'acide prussique dans la Bourse de Paris.

- 1 mai » à l'appel de l'American Federation of Labor, 350000travailleurs débrayent aux États-Unis pour réclamer la journée de travail de huit heures. Le massacre de Haymarket Square à Chicago constitue le point culminant de cette journée de lutte et un élément majeur de l'histoire de la fête des travailleurs du 1mai.

- 29 mai » première publicité pour le Coca-Cola, dans l'Atlanta Journal.

- 13 juin » grand incendie de Vancouver.

- 1 novembre » traité de délimitation anglo-allemand, qui fait tomber le Sultanat de Zanzibar sous l'influence britannique, mais reconnait à l'Allemagne une zone d'influence en Afrique orientale.

Même jour de naissance/décès

- 1761 » Antoine Barnave, homme politique français († 29 novembre 1793).

- 1764 » Jean-Marie Valhubert, militaire français († 3 décembre 1805).

- 1781 » Louis-Joseph de France, Dauphin de France, fils de Louis XVI. († 4 juin 1789)

- 1811 » Franz Liszt, compositeur hongrois († 31 juillet 1886).

- 1818 » Leconte de Lisle (Charles Marie René Leconte de Lisle, dit), poète français († 17 juillet 1894).

- 1844 » Louis Riel, homme politique canadien († 16 novembre 1885).

- 1864 » Louis Hachette, éditeur français (° 5 mai 1800).

- 1875 » Andrew Johnson, homme politique américain, 17président des États-Unis, ayant exercé de 1865 à 1869 (° 29 décembre 1808).

- 1886 » Franz Liszt, compositeur et pianiste hongrois (° 22 octobre 1811).

- 1897 » Auguste Lacaussade, poète français (° 8 février 1815).

- 1914 » Jean Jaurès, homme politique français (° 3 septembre 1859).

- 1933 » Shimizu Shikin, romancière et activiste japonaise (° 11 janvier 1868).

Sur le nom de famille Liszt

- Afficher les informations que Genealogie Online a concernant le patronyme Liszt.

- Afficher des informations sur Liszt sur le site Archives Ouvertes.

- Trouvez dans le registre Wie (onder)zoekt wie? qui recherche le nom de famille Liszt.

La publication Généalogie Kuipers a été préparée par T. Kuipers.

Lors de la copie des données de cet arbre généalogique, veuillez inclure une référence à l'origine:

T. Kuipers, "Généalogie Kuipers", base de données, Généalogie Online (https://www.genealogieonline.nl/genealogie_kuipers/I77806.php : consultée 24 juin 2024), "Franz Liszt (1811-1886)".

T. Kuipers, "Généalogie Kuipers", base de données, Généalogie Online (https://www.genealogieonline.nl/genealogie_kuipers/I77806.php : consultée 24 juin 2024), "Franz Liszt (1811-1886)".