maximum test » Henry "del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico" (1050-1106)

Persoonlijke gegevens Henry "del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico"

Bron 1- Roepnaam is del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico.

- Hij is geboren op 11 november 1050Brunswick Deutschland.

Let op: Leeftijd bij trouwen (13 juli 1066) lag beneden de 16 jaar (15).

Let op: Leeftijd bij trouwen (13 juli 1066) lag beneden de 16 jaar (15). - Beroepen:

- Keiser.

- Tysk keiser.

- Tysk-romersk kejsare (vandrade till Canossa).

- Empereur, Roi, de Germanie, d'Italie, Duc, de Bavière.

- Imperador do Sacro Império Romano.

- (Misc Event) in het jaar 1056.

- (Misc Event) in het jaar 1084.

- (Misc Event) in het jaar 1105.

- Hij is overleden op 7 augustus 1106, hij was toen 55 jaar oudLuttich

Duitsland. - Hij is begraven rond augustus 1111 in First at Liege, Belgium, and then unearthed and reburied at Speyer Cathedral, Speyer, Duitsland.

- Een kind van Heinrich "the Black/the Pious" Salier en Agnès

Gezin van Henry "del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico"

Hij is getrouwd met Bertha of Savoy.

Zij zijn getrouwd op 13 juli 1066, hij was toen 15 jaar oudTrebur

Hesse Duitsland.

Kind(eren):

Notities over Henry "del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico"

Name Suffix:Iv, Holy Roman Emperor

Konge av Tyskland 1056 - 1084.

Tysk-romersk keiser 1084 - 1105.

Heinrich ble konge av Tyskland 05.10.1056, men ble bortført i 1062 av erkebiskop

Anno av Køln og Otto av Nordheim. I 1065 ble han erklært for myndig etter initiativ av

erkebiskop Adalbert. Erkebiskopen satt Heinrich opp mot sachserne som gjorde opprør to

ganger, men de ble kuet etter Heinrichs seier ved Hohenburg 13.06.1075.

Pave Gregor VII, som hadde forenet seg med hans motstandere, erklærte Heinrich for

avsatt 24.06.1076 på synoden i Worms og lyste ham i bann. Han måtte ydmyke seg for

paven i Canossa i 1077, hvoretter bannstrålen ble tatt tilbake.

Det lyktes ham å felle motkongen, Rudolf av Schwaben, i 1080 og å avsette pave

Gregor VII. Han ble igjen bannlyst, men dro til Italien og inntok Roma i 1080. Her lot han seg

krone til keiser 31.03.1084 av motpaven, Clemens III.

I 1104 reiste hans sønn, Heinrich V, seg mot ham, og tvang ham til å ta avskjed i

Ingelheim 31.12.1105.

Heinrich ble gift 2. gang med Aupraxia, som døde i 1109.

Event: Crowned 31 MAR 1084 Holy Roman Emperor at Rome by Pope ClementIII 2 1

Event: Titled BET. 1055 - 1061 Duke of Bavaria [Henry VIII] 1

Event: Ruled BET. 1054 - 1084 King of Duitsland 1

Note:

Henry IV (b. Nov. 11, 1050, Goslar?, Saxony--d. Aug. 7, 1106, Liège, Lorraine), duke of Bavaria (as Henry VIII, 1055-61), German king (from1054), and Holy Roman emperor (1084-1105/06), who engaged in a long struggle with Hildebrand (Pope Gregory VII) on the question of lay investiture, eventually drawing excommunication on himself and doing penance at Canossa (1077). His last years were spent countering the rebellion of his sons Conrad and Henry (the future Henry V).

Early years.

Henry's father, Henry III, had retained a firm hold on the church andhad resolved a schism in Rome (1046), opening new activities for the reformers. At Easter 1051, the boy was baptized after the German princes had taken an oath of fidelity and obedience at Christmas 1050. On July 17, 1053, he was elected king at Tribur (modern Trebur, in Duitsland) on condition that he would be a just king. In 1054 he was crowned king in Aix-la-Chapelle (modern Aachen, in Germany), and the following year he became engaged to Bertha, daughter of the Margrave of Turin. When the Emperor died in October 1056, at the age of 39, succession to the throne and survival of the dynasty were assured. The princes of the realm raised no objection when nominal government was handed over to the six-year-old boy, for whom his pious and unworldly mother became regent. Yet the early death of Henry III was the beginning of a fateful change that marked all of his son's reign. In his will, the late emperor had appointed Pope Victor II as counsellor to the Empress, andthe Pope solved some of the conflicts between the princes and the imperial court that had endangered peace in the empire.

After Victor's early death (1057), however, the politically inept empress committed a number of decisive mistakes. On her own, and without the benefit of the advice of a permanent group of counsellors, she readily yielded to various influences. She turned over the duchy of Bavaria, which Henry III had given to his son in 1055, to the Saxon count Otto of Nordheim, thus depriving the king of an important foundation ofhis power. She gave the duchy of Swabia to Count Rudolf of Rheinfelden--who married her daughter--and the duchy of Carinthia to Count Berthold of Zähringen; both of them eventually became opponents of Henry IV. The death of the Emperor also marked the disruption of German influence in Italy and of the close relationship between the king and the reform popes. Their independence soon became apparent in the elections of Stephen IX and Nicholas II, which were not influenced (as under Henry III) by the German court; in the new procedure for the election of the popes (1059); and in the defensive alliance with the Normans in southern Italy. This alliance was necessary for the popes as an effective protection against the Romans and was not directed against the German king. Yet the Normans were considered usurpers and enemies of the Holy Roman Empire; the pact thus resulted in strained relations betweenthe Pope and the German court, and these strains were aggravated by papal claims and disciplinary action taken by Nicholas II against German bishops. While the German king had so far been known as a supporterof the reformers, the Empress now imprudently entered into an alliance with Italian opponents of church reform and brought about the election of Cadalus, bishop of Parma, as antipope (Honorius II) against thereigning pope, Alexander II, who had been elected by the reformers. But since she did not give effective support to Honorius, Alexander wasable to prevail. Her unwise church policy was matched by an obscurelymotivated submissive policy at home, which, by unwarranted cession ofholdings of the crown, weakened the material foundations of the king's power and, in addition, encouraged the rapacity of the nobles. Increasing discontent reached a climax in a conspiracy of the princes led by Anno, archbishop of Keulen, in April 1062. During a court assemblyin Kaiserswerth he kidnapped the young king and had him brought to Keulen by ship. Henry's attempt to escape by jumping into the Rhine failed. Agnes resigned as regent and the government was taken over by Anno, who settled the conflict with the church by recognizing Alexander II (1064). Anno was, however, too dominating and inflexible a man to win Henry's confidence, so that Adalbert, archbishop of Bremen, granting more freedom to the lascivious young king, gained increasing and finally sole influence. But he used it for such unscrupulous personal enrichment that Henry, who was declared of age in 1065, had to ban him from court early in 1066. This incident marks the beginning of the King's own rule, for which he was badly prepared. Repeated changes in the government of the empire had an unsettling effect on the boy king and had, moreover, prevented him from being given a regular education. Theselfishness of his tutors, the dissolute character of his companions,and the traumatic experience of his kidnapping had produced a lack ofmoral stability during his years of puberty. In addition, his love ofpower, typical of all the rulers of his dynasty, contributed to conduct often characterized by recklessness and indiscretion.

In 1069, after three years of marriage, he suddenly announced his intention of divorcing his wife, Bertha. Following protests by high church dignitaries, he dropped his plan, but his mercurial behaviour incurred the displeasure of the reformers. At the same time he was faced with domestic difficulties that were to harass him throughout his reign.After his mother had freely dispensed of lands during her regency, hebegan to increase the royal possessions in the Harz Mountains and to protect them by castles, which he handed over to Swabian ministerials (higher civil servants directly responsible to the crown). Peasants and nobles in Saxony were stirred up by the ruthless repossession of former royal rights that had long ago been appropriated by nobility or had become obsolete and by the high-handed and severe measures of the foreign ministerials. Henry tried to stop the unrest by imprisoning Magnus, the duke of Saxony, and by depriving the widely respected Otto ofBavaria of his duchy, after having unjustly accused him of plotting the murder of the King (1070). Then a rebellion broke out among the Saxons, which in 1073 spread so rapidly that Henry had to escape to Worms. After negotiations with Welf IV, the new duke (as Welf I) of Bavaria, and with Rudolf, the duke of Swabia, Henry was forced to grant immunity to the rebels in 1073 and had to agree to the razing of the royalHarz Castle in the final peace treaty in February 1074. When the peasants, destroying the castle, also desecrated the church and the tomb of one of the King's sons, Henry declared the peace broken. This incident assured him of support from all over the empire, and in June 1075 he won an overwhelming victory that resulted in the surrender of the Saxons. It also forced the princes at Christmas to confirm on oath the succession of his one-year-old son, Conrad.

Role in investiture conflict.

This rebellion affected relations between Henry and the Pope. In Milan a popular party, the Patarines, dedicated to reforming the city's corrupt higher clergy, elected its own archbishop, who was recognized by the Pope. When Henry countered by having his own nominee consecrated by the Lombard bishops, Alexander II excommunicated the bishops. Henry did not yield, and it was not until the Saxon rebellion that he was ready to negotiate. In 1073 he humbly asked the new pope, Gregory VII, to settle the Milan problem. The King having thus renounced his right of investiture, a Roman synod, called to strengthen the Patarine movement, forbade any lay investiture in Milan; henceforward Gregory regarded Henry as his ally in questions of church reform. When planninga crusade, he even put the defense of the Roman Church into the King's hands. But after defeating the Saxons, Henry considered himself strong enough to cancel his agreements with the Pope and to nominate his court chaplain as archbishop of Milan. The violation of the agreement on investiture called into question the King's trustworthiness, and the Pope sent him a letter warning him of the melancholy fate of King Saul (after breaking with his church in the person of the prophet Samuel) but offering negotiations on the investiture problem. Instead of accepting the offer, which arrived at his court on Jan. 1, 1076, Henry, on the same day, deposed the Pope and persuaded an assembly of 26 bishops, hastily called to Worms, to refuse obedience to the Pope. By thisimpulsive reaction he turned the problem of investiture in Milan, which could have been solved by negotiations, into a fundamental dispute on the relations between church and state. Gregory replied by excommunicating Henry and absolving the King's subjects from their oaths of allegiance. Such action equalled dethronement. Many bishops who had taken part in the Worms assembly and had subsequently been excommunicatednow surrendered to the Pope, and immediately the King was also faced with the newly aroused opposition of the nobility. In October 1076 theprinces discussed the election of a new king in Tribur. It was only by promising to seek absolution from the ban within a year that Henry could reach a postponement of the election. The final decision was to be taken at an assembly to be called at Augsburg to which the Pope wasalso invited. But Henry secretly travelled to northern Italy and in Canossa did penance before Gregory VII, whereupon he was readmitted to the church. For the moment it was a political success for the King because the opposition had been deprived of all canonical arguments. Yet,Canossa meant a change. By doing penance Henry had admitted the legality of the Pope's measures and had given up the king's traditional position of authority equal or even superior to that of the church. The relations between church and state were changed forever.

The princes, however, considered Canossa a breach of the original agreement providing for an assembly at Augsburg and declared Henry dethroned. In his stead, they elected Rudolf, duke of Swabia, in March 1077,whereupon Henry confiscated the duchies of Bavaria and Swabia on behalf of the crown. He received support from the peasants and citizens ofthese duchies, whereas Rudolf relied mainly on the Saxons. Gregory watched the indecisive struggle between Henry and Rudolf for almost three years until he resolved to bring about a decision for the sake of continued church reform in Duitsland. At a synod in March 1080, he prohibited investiture, excommunicated and dethroned Henry again, and recognized Rudolf. The reasons for this act of excommunication were not as valid as those advanced in 1077, and many nobles who had so far favoured the Pope turned against him because they thought the prohibition ofinvestiture infringed upon their rights as patrons of churches and monasteries. Henry now succeeded in deposing Gregory and in nominating Guibert, archbishop of Ravenna, as pope at a synod in Brixen (Bressanone). When the opposition of the princes was crippled by the death of Rudolf in October 1080, Henry, freed of the threat of enemies to the rear, went to Italy to seek a military decision in his struggle with the church. After attacking Rome in vain in 1081 and 1082, he conquered the city in March 1084. Guibert was enthroned as Clement III and crowned Henry emperor on March 31, 1084. Gregory, the legitimate pope, fledto Salerno, where he died on May 25, 1085. A number of cardinals joined Clement, and, feeling that he had won a complete victory, the Emperor returned to Duitsland. In May 1087 he had his son Conrad crowned king. The Saxons now made peace with him. Further, Henry replaced bishopswho did not join Clement with others loyal to the King.

Later crises in Italy and Duitsland.

The escape and death of Gregory VII and the presence of Clement III in Rome caused a crisis in the reform movement of the church, from which, however, it quickly recovered under the pontificate of Urban II (1088-1099). The marriage, arranged by Urban in 1089, of the 17-year-oldWelf V of Bavaria with the 43-year-old countess Matilda of Tuscany, azealous adherent of the cause of reform in the church, allied Henry'sopponents in southern Duitsland and Italy. Henry was forced to invade Italy once more in 1090, but, after initial success, his defeat in 1092resulted in the uprisings in Lombardy; and the rebellion of his son Conrad, who was crowned king of Italy by the Lombards, led to general rebellion. The Emperor found himself cut off from Duitsland and besieged in a corner of northeastern Italy. In addition, his second wife, Praxedis of Kiev, whom he had married in 1089 after the death of Bertha in 1087, left him, bringing serious charges against him. It was not untilWelf V separated from Matilda, in 1095, and his father, the deposed Welf IV, was once more granted Bavaria as a fief, in 1096, that Henry was able to return to Duitsland (1097). In Duitsland sympathy for reform and the papacy no longer excluded loyalty to the Emperor.

Gradually Henry was able to consolidate his authority so that in May 1098 the princes elected his second son, Henry V, king in place of thedisloyal Conrad. But peace with the Pope, which was necessary for a complete consolidation of authority, was a goal that remained unattainable. At first a settlement was impossible because of Henry's support for Clement III, who had died in 1100. Paschal II (1099-1118), a follower of the reformist policies of Gregory VII, was unwilling to concludean agreement with Henry. Finally, the Emperor declared that he would go on a crusade if his excommunication were removed. To prepare for the crusade, he forbade all feuds among the great nobles of the empire for four years (1103). But unrest started again when reconciliation with the church did not materialize and the nobles thought the Emperor was restricting their rights in favour of his son. Henry V feared a controversy with the princes. In alliance with Bavarian nobles he revolted against the Emperor in 1104 to secure his throne by sacrificing hisfather. The Emperor escaped to Keulen, but when he went to Mainz hisson imprisoned him and on Dec. 31, 1105, extorted his apparently voluntary abdication. Henry IV, however, was not yet prepared to give up. He fled to Liège and with the Lotharingians defeated Henry V's army near Visé on March 22, 1106. Henry IV suddenly died in Liège on August 7. His body was transferred to Speyer but remained there in an unconsecrated chapel before being buried in the family vault in 1111.

Assessment.

Judgment of Henry by his contemporaries differed according to the parties to which they belonged. His opponents considered the tall, handsome king a tyrant--the crafty head of heresy--whose death they cheered because it seemed to usher in a new age. His friends praised him as a pious, gentle, and intelligent ruler, a patron of the arts and sciences, who surrounded himself with religious scholars and who, in his sense of law and justice, was the embodiment of the ideal king. In his attempt to preserve the traditional rights of the crown, Henry IV was only partially successful, for while he strengthened the king's positionagainst the nobles by gaining the support of the peasants, the citizens, and the ministerials, his continuing battles with the reforming church over investiture ultimately weakened royal influence over the papacy. [Encyclopaedia Britannica CD '97]

Event: Crowned 31 MAR 1084 Holy Roman Emperor at Rome by Pope ClementIII 2 1

Event: Titled BET. 1055 - 1061 Duke of Bavaria [Henry VIII] 1

Event: Ruled BET. 1054 - 1084 King of Duitsland 1

Note:

Henry IV (b. Nov. 11, 1050, Goslar?, Saxony--d. Aug. 7, 1106, Liège, Lorraine), duke of Bavaria (as Henry VIII, 1055-61), German king (from1054), and Holy Roman emperor (1084-1105/06), who engaged in a long struggle with Hildebrand (Pope Gregory VII) on the question of lay investiture, eventually drawing excommunication on himself and doing penance at Canossa (1077). His last years were spent countering the rebellion of his sons Conrad and Henry (the future Henry V).

Early years.

Henry's father, Henry III, had retained a firm hold on the church andhad resolved a schism in Rome (1046), opening new activities for the reformers. At Easter 1051, the boy was baptized after the German princes had taken an oath of fidelity and obedience at Christmas 1050. On July 17, 1053, he was elected king at Tribur (modern Trebur, in Duitsland) on condition that he would be a just king. In 1054 he was crowned king in Aix-la-Chapelle (modern Aachen, in Germany), and the following year he became engaged to Bertha, daughter of the Margrave of Turin. When the Emperor died in October 1056, at the age of 39, succession to the throne and survival of the dynasty were assured. The princes of the realm raised no objection when nominal government was handed over to the six-year-old boy, for whom his pious and unworldly mother became regent. Yet the early death of Henry III was the beginning of a fateful change that marked all of his son's reign. In his will, the late emperor had appointed Pope Victor II as counsellor to the Empress, andthe Pope solved some of the conflicts between the princes and the imperial court that had endangered peace in the empire.

After Victor's early death (1057), however, the politically inept empress committed a number of decisive mistakes. On her own, and without the benefit of the advice of a permanent group of counsellors, she readily yielded to various influences. She turned over the duchy of Bavaria, which Henry III had given to his son in 1055, to the Saxon count Otto of Nordheim, thus depriving the king of an important foundation ofhis power. She gave the duchy of Swabia to Count Rudolf of Rheinfelden--who married her daughter--and the duchy of Carinthia to Count Berthold of Zähringen; both of them eventually became opponents of Henry IV. The death of the Emperor also marked the disruption of German influence in Italy and of the close relationship between the king and the reform popes. Their independence soon became apparent in the elections of Stephen IX and Nicholas II, which were not influenced (as under Henry III) by the German court; in the new procedure for the election of the popes (1059); and in the defensive alliance with the Normans in southern Italy. This alliance was necessary for the popes as an effective protection against the Romans and was not directed against the German king. Yet the Normans were considered usurpers and enemies of the Holy Roman Empire; the pact thus resulted in strained relations betweenthe Pope and the German court, and these strains were aggravated by papal claims and disciplinary action taken by Nicholas II against German bishops. While the German king had so far been known as a supporterof the reformers, the Empress now imprudently entered into an alliance with Italian opponents of church reform and brought about the election of Cadalus, bishop of Parma, as antipope (Honorius II) against thereigning pope, Alexander II, who had been elected by the reformers. But since she did not give effective support to Honorius, Alexander wasable to prevail. Her unwise church policy was matched by an obscurelymotivated submissive policy at home, which, by unwarranted cession ofholdings of the crown, weakened the material foundations of the king's power and, in addition, encouraged the rapacity of the nobles. Increasing discontent reached a climax in a conspiracy of the princes led by Anno, archbishop of Keulen, in April 1062. During a court assemblyin Kaiserswerth he kidnapped the young king and had him brought to Keulen by ship. Henry's attempt to escape by jumping into the Rhine failed. Agnes resigned as regent and the government was taken over by Anno, who settled the conflict with the church by recognizing Alexander II (1064). Anno was, however, too dominating and inflexible a man to win Henry's confidence, so that Adalbert, archbishop of Bremen, granting more freedom to the lascivious young king, gained increasing and finally sole influence. But he used it for such unscrupulous personal enrichment that Henry, who was declared of age in 1065, had to ban him from court early in 1066. This incident marks the beginning of the King's own rule, for which he was badly prepared. Repeated changes in the government of the empire had an unsettling effect on the boy king and had, moreover, prevented him from being given a regular education. Theselfishness of his tutors, the dissolute character of his companions,and the traumatic experience of his kidnapping had produced a lack ofmoral stability during his years of puberty. In addition, his love ofpower, typical of all the rulers of his dynasty, contributed to conduct often characterized by recklessness and indiscretion.

In 1069, after three years of marriage, he suddenly announced his intention of divorcing his wife, Bertha. Following protests by high church dignitaries, he dropped his plan, but his mercurial behaviour incurred the displeasure of the reformers. At the same time he was faced with domestic difficulties that were to harass him throughout his reign.After his mother had freely dispensed of lands during her regency, hebegan to increase the royal possessions in the Harz Mountains and to protect them by castles, which he handed over to Swabian ministerials (higher civil servants directly responsible to the crown). Peasants and nobles in Saxony were stirred up by the ruthless repossession of former royal rights that had long ago been appropriated by nobility or had become obsolete and by the high-handed and severe measures of the foreign ministerials. Henry tried to stop the unrest by imprisoning Magnus, the duke of Saxony, and by depriving the widely respected Otto ofBavaria of his duchy, after having unjustly accused him of plotting the murder of the King (1070). Then a rebellion broke out among the Saxons, which in 1073 spread so rapidly that Henry had to escape to Worms. After negotiations with Welf IV, the new duke (as Welf I) of Bavaria, and with Rudolf, the duke of Swabia, Henry was forced to grant immunity to the rebels in 1073 and had to agree to the razing of the royalHarz Castle in the final peace treaty in February 1074. When the peasants, destroying the castle, also desecrated the church and the tomb of one of the King's sons, Henry declared the peace broken. This incident assured him of support from all over the empire, and in June 1075 he won an overwhelming victory that resulted in the surrender of the Saxons. It also forced the princes at Christmas to confirm on oath the succession of his one-year-old son, Conrad.

Role in investiture conflict.

This rebellion affected relations between Henry and the Pope. In Milan a popular party, the Patarines, dedicated to reforming the city's corrupt higher clergy, elected its own archbishop, who was recognized by the Pope. When Henry countered by having his own nominee consecrated by the Lombard bishops, Alexander II excommunicated the bishops. Henry did not yield, and it was not until the Saxon rebellion that he was ready to negotiate. In 1073 he humbly asked the new pope, Gregory VII, to settle the Milan problem. The King having thus renounced his right of investiture, a Roman synod, called to strengthen the Patarine movement, forbade any lay investiture in Milan; henceforward Gregory regarded Henry as his ally in questions of church reform. When planninga crusade, he even put the defense of the Roman Church into the King's hands. But after defeating the Saxons, Henry considered himself strong enough to cancel his agreements with the Pope and to nominate his court chaplain as archbishop of Milan. The violation of the agreement on investiture called into question the King's trustworthiness, and the Pope sent him a letter warning him of the melancholy fate of King Saul (after breaking with his church in the person of the prophet Samuel) but offering negotiations on the investiture problem. Instead of accepting the offer, which arrived at his court on Jan. 1, 1076, Henry, on the same day, deposed the Pope and persuaded an assembly of 26 bishops, hastily called to Worms, to refuse obedience to the Pope. By thisimpulsive reaction he turned the problem of investiture in Milan, which could have been solved by negotiations, into a fundamental dispute on the relations between church and state. Gregory replied by excommunicating Henry and absolving the King's subjects from their oaths of allegiance. Such action equalled dethronement. Many bishops who had taken part in the Worms assembly and had subsequently been excommunicatednow surrendered to the Pope, and immediately the King was also faced with the newly aroused opposition of the nobility. In October 1076 theprinces discussed the election of a new king in Tribur. It was only by promising to seek absolution from the ban within a year that Henry could reach a postponement of the election. The final decision was to be taken at an assembly to be called at Augsburg to which the Pope wasalso invited. But Henry secretly travelled to northern Italy and in Canossa did penance before Gregory VII, whereupon he was readmitted to the church. For the moment it was a political success for the King because the opposition had been deprived of all canonical arguments. Yet,Canossa meant a change. By doing penance Henry had admitted the legality of the Pope's measures and had given up the king's traditional position of authority equal or even superior to that of the church. The relations between church and state were changed forever.

The princes, however, considered Canossa a breach of the original agreement providing for an assembly at Augsburg and declared Henry dethroned. In his stead, they elected Rudolf, duke of Swabia, in March 1077,whereupon Henry confiscated the duchies of Bavaria and Swabia on behalf of the crown. He received support from the peasants and citizens ofthese duchies, whereas Rudolf relied mainly on the Saxons. Gregory watched the indecisive struggle between Henry and Rudolf for almost three years until he resolved to bring about a decision for the sake of continued church reform in Duitsland. At a synod in March 1080, he prohibited investiture, excommunicated and dethroned Henry again, and recognized Rudolf. The reasons for this act of excommunication were not as valid as those advanced in 1077, and many nobles who had so far favoured the Pope turned against him because they thought the prohibition ofinvestiture infringed upon their rights as patrons of churches and monasteries. Henry now succeeded in deposing Gregory and in nominating Guibert, archbishop of Ravenna, as pope at a synod in Brixen (Bressanone). When the opposition of the princes was crippled by the death of Rudolf in October 1080, Henry, freed of the threat of enemies to the rear, went to Italy to seek a military decision in his struggle with the church. After attacking Rome in vain in 1081 and 1082, he conquered the city in March 1084. Guibert was enthroned as Clement III and crowned Henry emperor on March 31, 1084. Gregory, the legitimate pope, fledto Salerno, where he died on May 25, 1085. A number of cardinals joined Clement, and, feeling that he had won a complete victory, the Emperor returned to Duitsland. In May 1087 he had his son Conrad crowned king. The Saxons now made peace with him. Further, Henry replaced bishopswho did not join Clement with others loyal to the King.

Later crises in Italy and Duitsland.

The escape and death of Gregory VII and the presence of Clement III in Rome caused a crisis in the reform movement of the church, from which, however, it quickly recovered under the pontificate of Urban II (1088-1099). The marriage, arranged by Urban in 1089, of the 17-year-oldWelf V of Bavaria with the 43-year-old countess Matilda of Tuscany, azealous adherent of the cause of reform in the church, allied Henry'sopponents in southern Duitsland and Italy. Henry was forced to invade Italy once more in 1090, but, after initial success, his defeat in 1092resulted in the uprisings in Lombardy; and the rebellion of his son Conrad, who was crowned king of Italy by the Lombards, led to general rebellion. The Emperor found himself cut off from Duitsland and besieged in a corner of northeastern Italy. In addition, his second wife, Praxedis of Kiev, whom he had married in 1089 after the death of Bertha in 1087, left him, bringing serious charges against him. It was not untilWelf V separated from Matilda, in 1095, and his father, the deposed Welf IV, was once more granted Bavaria as a fief, in 1096, that Henry was able to return to Duitsland (1097). In Duitsland sympathy for reform and the papacy no longer excluded loyalty to the Emperor.

Gradually Henry was able to consolidate his authority so that in May 1098 the princes elected his second son, Henry V, king in place of thedisloyal Conrad. But peace with the Pope, which was necessary for a complete consolidation of authority, was a goal that remained unattainable. At first a settlement was impossible because of Henry's support for Clement III, who had died in 1100. Paschal II (1099-1118), a follower of the reformist policies of Gregory VII, was unwilling to concludean agreement with Henry. Finally, the Emperor declared that he would go on a crusade if his excommunication were removed. To prepare for the crusade, he forbade all feuds among the great nobles of the empire for four years (1103). But unrest started again when reconciliation with the church did not materialize and the nobles thought the Emperor was restricting their rights in favour of his son. Henry V feared a controversy with the princes. In alliance with Bavarian nobles he revolted against the Emperor in 1104 to secure his throne by sacrificing hisfather. The Emperor escaped to Keulen, but when he went to Mainz hisson imprisoned him and on Dec. 31, 1105, extorted his apparently voluntary abdication. Henry IV, however, was not yet prepared to give up. He fled to Liège and with the Lotharingians defeated Henry V's army near Visé on March 22, 1106. Henry IV suddenly died in Liège on August 7. His body was transferred to Speyer but remained there in an unconsecrated chapel before being buried in the family vault in 1111.

Assessment.

Judgment of Henry by his contemporaries differed according to the parties to which they belonged. His opponents considered the tall, handsome king a tyrant--the crafty head of heresy--whose death they cheered because it seemed to usher in a new age. His friends praised him as a pious, gentle, and intelligent ruler, a patron of the arts and sciences, who surrounded himself with religious scholars and who, in his sense of law and justice, was the embodiment of the ideal king. In his attempt to preserve the traditional rights of the crown, Henry IV was only partially successful, for while he strengthened the king's positionagainst the nobles by gaining the support of the peasants, the citizens, and the ministerials, his continuing battles with the reforming church over investiture ultimately weakened royal influence over the papacy. [Encyclopaedia Britannica CD '97]

Event: Crowned 31 MAR 1084 Holy Roman Emperor at Rome by Pope ClementIII 2 1

Event: Titled BET. 1055 - 1061 Duke of Bavaria [Henry VIII] 1

Event: Ruled BET. 1054 - 1084 King of Duitsland 1

Note:

Henry IV (b. Nov. 11, 1050, Goslar?, Saxony--d. Aug. 7, 1106, Liège, Lorraine), duke of Bavaria (as Henry VIII, 1055-61), German king (from1054), and Holy Roman emperor (1084-1105/06), who engaged in a long struggle with Hildebrand (Pope Gregory VII) on the question of lay investiture, eventually drawing excommunication on himself and doing penance at Canossa (1077). His last years were spent countering the rebellion of his sons Conrad and Henry (the future Henry V).

Early years.

Henry's father, Henry III, had retained a firm hold on the church andhad resolved a schism in Rome (1046), opening new activities for the reformers. At Easter 1051, the boy was baptized after the German princes had taken an oath of fidelity and obedience at Christmas 1050. On July 17, 1053, he was elected king at Tribur (modern Trebur, in Duitsland) on condition that he would be a just king. In 1054 he was crowned king in Aix-la-Chapelle (modern Aachen, in Germany), and the following year he became engaged to Bertha, daughter of the Margrave of Turin. When the Emperor died in October 1056, at the age of 39, succession to the throne and survival of the dynasty were assured. The princes of the realm raised no objection when nominal government was handed over to the six-year-old boy, for whom his pious and unworldly mother became regent. Yet the early death of Henry III was the beginning of a fateful change that marked all of his son's reign. In his will, the late emperor had appointed Pope Victor II as counsellor to the Empress, andthe Pope solved some of the conflicts between the princes and the imperial court that had endangered peace in the empire.

After Victor's early death (1057), however, the politically inept empress committed a number of decisive mistakes. On her own, and without the benefit of the advice of a permanent group of counsellors, she readily yielded to various influences. She turned over the duchy of Bavaria, which Henry III had given to his son in 1055, to the Saxon count Otto of Nordheim, thus depriving the king of an important foundation ofhis power. She gave the duchy of Swabia to Count Rudolf of Rheinfelden--who married her daughter--and the duchy of Carinthia to Count Berthold of Zähringen; both of them eventually became opponents of Henry IV. The death of the Emperor also marked the disruption of German influence in Italy and of the close relationship between the king and the reform popes. Their independence soon became apparent in the elections of Stephen IX and Nicholas II, which were not influenced (as under Henry III) by the German court; in the new procedure for the election of the popes (1059); and in the defensive alliance with the Normans in southern Italy. This alliance was necessary for the popes as an effective protection against the Romans and was not directed against the German king. Yet the Normans were considered usurpers and enemies of the Holy Roman Empire; the pact thus resulted in strained relations betweenthe Pope and the German court, and these strains were aggravated by papal claims and disciplinary action taken by Nicholas II against German bishops. While the German king had so far been known as a supporterof the reformers, the Empress now imprudently entered into an alliance with Italian opponents of church reform and brought about the election of Cadalus, bishop of Parma, as antipope (Honorius II) against thereigning pope, Alexander II, who had been elected by the reformers. But since she did not give effective support to Honorius, Alexander wasable to prevail. Her unwise church policy was matched by an obscurelymotivated submissive policy at home, which, by unwarranted cession ofholdings of the crown, weakened the material foundations of the king's power and, in addition, encouraged the rapacity of the nobles. Increasing discontent reached a climax in a conspiracy of the princes led by Anno, archbishop of Keulen, in April 1062. During a court assemblyin Kaiserswerth he kidnapped the young king and had him brought to Keulen by ship. Henry's attempt to escape by jumping into the Rhine failed. Agnes resigned as regent and the government was taken over by Anno, who settled the conflict with the church by recognizing Alexander II (1064). Anno was, however, too dominating and inflexible a man to win Henry's confidence, so that Adalbert, archbishop of Bremen, granting more freedom to the lascivious young king, gained increasing and finally sole influence. But he used it for such unscrupulous personal enrichment that Henry, who was declared of age in 1065, had to ban him from court early in 1066. This incident marks the beginning of the King's own rule, for which he was badly prepared. Repeated changes in the government of the empire had an unsettling effect on the boy king and had, moreover, prevented him from being given a regular education. Theselfishness of his tutors, the dissolute character of his companions,and the traumatic experience of his kidnapping had produced a lack ofmoral stability during his years of puberty. In addition, his love ofpower, typical of all the rulers of his dynasty, contributed to conduct often characterized by recklessness and indiscretion.

In 1069, after three years of marriage, he suddenly announced his intention of divorcing his wife, Bertha. Following protests by high church dignitaries, he dropped his plan, but his mercurial behaviour incurred the displeasure of the reformers. At the same time he was faced with domestic difficulties that were to harass him throughout his reign.After his mother had freely dispensed of lands during her regency, hebegan to increase the royal possessions in the Harz Mountains and to protect them by castles, which he handed over to Swabian ministerials (higher civil servants directly responsible to the crown). Peasants and nobles in Saxony were stirred up by the ruthless repossession of former royal rights that had long ago been appropriated by nobility or had become obsolete and by the high-handed and severe measures of the foreign ministerials. Henry tried to stop the unrest by imprisoning Magnus, the duke of Saxony, and by depriving the widely respected Otto ofBavaria of his duchy, after having unjustly accused him of plotting the murder of the King (1070). Then a rebellion broke out among the Saxons, which in 1073 spread so rapidly that Henry had to escape to Worms. After negotiations with Welf IV, the new duke (as Welf I) of Bavaria, and with Rudolf, the duke of Swabia, Henry was forced to grant immunity to the rebels in 1073 and had to agree to the razing of the royalHarz Castle in the final peace treaty in February 1074. When the peasants, destroying the castle, also desecrated the church and the tomb of one of the King's sons, Henry declared the peace broken. This incident assured him of support from all over the empire, and in June 1075 he won an overwhelming victory that resulted in the surrender of the Saxons. It also forced the princes at Christmas to confirm on oath the succession of his one-year-old son, Conrad.

Role in investiture conflict.

This rebellion affected relations between Henry and the Pope. In Milan a popular party, the Patarines, dedicated to reforming the city's corrupt higher clergy, elected its own archbishop, who was recognized by the Pope. When Henry countered by having his own nominee consecrated by the Lombard bishops, Alexander II excommunicated the bishops. Henry did not yield, and it was not until the Saxon rebellion that he was ready to negotiate. In 1073 he humbly asked the new pope, Gregory VII, to settle the Milan problem. The King having thus renounced his right of investiture, a Roman synod, called to strengthen the Patarine movement, forbade any lay investiture in Milan; henceforward Gregory regarded Henry as his ally in questions of church reform. When planninga crusade, he even put the defense of the Roman Church into the King's hands. But after defeating the Saxons, Henry considered himself strong enough to cancel his agreements with the Pope and to nominate his court chaplain as archbishop of Milan. The violation of the agreement on investiture called into question the King's trustworthiness, and the Pope sent him a letter warning him of the melancholy fate of King Saul (after breaking with his church in the person of the prophet Samuel) but offering negotiations on the investiture problem. Instead of accepting the offer, which arrived at his court on Jan. 1, 1076, Henry, on the same day, deposed the Pope and persuaded an assembly of 26 bishops, hastily called to Worms, to refuse obedience to the Pope. By thisimpulsive reaction he turned the problem of investiture in Milan, which could have been solved by negotiations, into a fundamental dispute on the relations between church and state. Gregory replied by excommunicating Henry and absolving the King's subjects from their oaths of allegiance. Such action equalled dethronement. Many bishops who had taken part in the Worms assembly and had subsequently been excommunicatednow surrendered to the Pope, and immediately the King was also faced with the newly aroused opposition of the nobility. In October 1076 theprinces discussed the election of a new king in Tribur. It was only by promising to seek absolution from the ban within a year that Henry could reach a postponement of the election. The final decision was to be taken at an assembly to be called at Augsburg to which the Pope wasalso invited. But Henry secretly travelled to northern Italy and in Canossa did penance before Gregory VII, whereupon he was readmitted to the church. For the moment it was a political success for the King because the opposition had been deprived of all canonical arguments. Yet,Canossa meant a change. By doing penance Henry had admitted the legality of the Pope's measures and had given up the king's traditional position of authority equal or even superior to that of the church. The relations between church and state were changed forever.

The princes, however, considered Canossa a breach of the original agreement providing for an assembly at Augsburg and declared Henry dethroned. In his stead, they elected Rudolf, duke of Swabia, in March 1077,whereupon Henry confiscated the duchies of Bavaria and Swabia on behalf of the crown. He received support from the peasants and citizens ofthese duchies, whereas Rudolf relied mainly on the Saxons. Gregory watched the indecisive struggle between Henry and Rudolf for almost three years until he resolved to bring about a decision for the sake of continued church reform in Duitsland. At a synod in March 1080, he prohibited investiture, excommunicated and dethroned Henry again, and recognized Rudolf. The reasons for this act of excommunication were not as valid as those advanced in 1077, and many nobles who had so far favoured the Pope turned against him because they thought the prohibition ofinvestiture infringed upon their rights as patrons of churches and monasteries. Henry now succeeded in deposing Gregory and in nominating Guibert, archbishop of Ravenna, as pope at a synod in Brixen (Bressanone). When the opposition of the princes was crippled by the death of Rudolf in October 1080, Henry, freed of the threat of enemies to the rear, went to Italy to seek a military decision in his struggle with the church. After attacking Rome in vain in 1081 and 1082, he conquered the city in March 1084. Guibert was enthroned as Clement III and crowned Henry emperor on March 31, 1084. Gregory, the legitimate pope, fledto Salerno, where he died on May 25, 1085. A number of cardinals joined Clement, and, feeling that he had won a complete victory, the Emperor returned to Duitsland. In May 1087 he had his son Conrad crowned king. The Saxons now made peace with him. Further, Henry replaced bishopswho did not join Clement with others loyal to the King.

Later crises in Italy and Duitsland.

The escape and death of Gregory VII and the presence of Clement III in Rome caused a crisis in the reform movement of the church, from which, however, it quickly recovered under the pontificate of Urban II (1088-1099). The marriage, arranged by Urban in 1089, of the 17-year-oldWelf V of Bavaria with the 43-year-old countess Matilda of Tuscany, azealous adherent of the cause of reform in the church, allied Henry'sopponents in southern Duitsland and Italy. Henry was forced to invade Italy once more in 1090, but, after initial success, his defeat in 1092resulted in the uprisings in Lombardy; and the rebellion of his son Conrad, who was crowned king of Italy by the Lombards, led to general rebellion. The Emperor found himself cut off from Duitsland and besieged in a corner of northeastern Italy. In addition, his second wife, Praxedis of Kiev, whom he had married in 1089 after the death of Bertha in 1087, left him, bringing serious charges against him. It was not untilWelf V separated from Matilda, in 1095, and his father, the deposed Welf IV, was once more granted Bavaria as a fief, in 1096, that Henry was able to return to Duitsland (1097). In Duitsland sympathy for reform and the papacy no longer excluded loyalty to the Emperor.

Gradually Henry was able to consolidate his authority so that in May 1098 the princes elected his second son, Henry V, king in place of thedisloyal Conrad. But peace with the Pope, which was necessary for a complete consolidation of authority, was a goal that remained unattainable. At first a settlement was impossible because of Henry's support for Clement III, who had died in 1100. Paschal II (1099-1118), a follower of the reformist policies of Gregory VII, was unwilling to concludean agreement with Henry. Finally, the Emperor declared that he would go on a crusade if his excommunication were removed. To prepare for the crusade, he forbade all feuds among the great nobles of the empire for four years (1103). But unrest started again when reconciliation with the church did not materialize and the nobles thought the Emperor was restricting their rights in favour of his son. Henry V feared a controversy with the princes. In alliance with Bavarian nobles he revolted against the Emperor in 1104 to secure his throne by sacrificing hisfather. The Emperor escaped to Keulen, but when he went to Mainz hisson imprisoned him and on Dec. 31, 1105, extorted his apparently voluntary abdication. Henry IV, however, was not yet prepared to give up. He fled to Liège and with the Lotharingians defeated Henry V's army near Visé on March 22, 1106. Henry IV suddenly died in Liège on August 7. His body was transferred to Speyer but remained there in an unconsecrated chapel before being buried in the family vault in 1111.

Assessment.

Judgment of Henry by his contemporaries differed according to the parties to which they belonged. His opponents considered the tall, handsome king a tyrant--the crafty head of heresy--whose death they cheered because it seemed to usher in a new age. His friends praised him as a pious, gentle, and intelligent ruler, a patron of the arts and sciences, who surrounded himself with religious scholars and who, in his sense of law and justice, was the embodiment of the ideal king. In his attempt to preserve the traditional rights of the crown, Henry IV was only partially successful, for while he strengthened the king's positionagainst the nobles by gaining the support of the peasants, the citizens, and the ministerials, his continuing battles with the reforming church over investiture ultimately weakened royal influence over the papacy. [Encyclopaedia Britannica CD '97]

Duke of Bavaria as Henry VIII, 1055-1061. Coming of age to rule on his own in

1065 after a terrible series of regents, Henry himself was badly prepared for

the job ahead. Henry was only partially successful during his reign, for

while he strengthened the king's position against the nobles by gaining the

support of the peasants, the citizens, and the ministerials, his continuing

battles with the reforming church over investiture ultimately weakened royal

influence over the papacy.

Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Henry IV

King of Duitsland, Holy Roman Emperor

Reign 1084 – 1105

Born 11 November 1050(1050-11-11)

Royal palace at Goslar

Died 7 August 1106 (aged 55)

Buried Speyer Cathedral

Predecessor Henry III

Successor Henry V

Father Henry III

Mother Agnes de Poitou

Henry IV (November 11, 1050–August 7, 1106) was King of Duitsland from 1056 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1084 until his forced abdication in 1105. He was the third emperor of the Salian dynasty and one of the most powerful and important figures of the 11th century. His reign was marked by the Investiture Controversy with the Papacy and several civil wars with pretenders to his throne in Italy and Duitsland.

Contents [hide]

1 Biography

1.1 Regency

1.2 First years of rule and Saxon War

1.3 Investiture Controversy

1.4 Civil war and recovery

1.5 Second voyage to Italy

1.6 Internecine wars and death

2 Evaluation

3 Marriages

4 Henry IV in fiction

5 Notes

6 Sources

[edit] Biography

[edit] Regency

Henry was the eldest son of the Emperor Henry III, by his second wife Agnes de Poitou, and was probably born at the royal palace at Goslar. His christening was delayed until the following Easter so that Abbot Hugh of Cluny could be one of his godparents. But even before that, at his Christmas court Henry III induced the attending nobles to promise fidelity to his son. Three years later, still anxious to ensure the succession, Henry III had a larger assembly of nobles elect the young Henry as his successor, and then, on July 17, 1054, had him elected as king by Herman II, Archbishop of Keulen at Trebur. The coronation was held in Aachen in 1054. When Henry III unexpectedly died in 1056, the accession of the six-year-old Henry IV was not opposed by his vassals. The dowager Empress Agnes acted as regent, and, according to the will of the dead emperor, the German pope Victor II was named as her counsellor. The latter's death in 1057 soon showed the political ineptitude of Agnes, and the powerful influence held over her by German magnates and Imperial functionaries.

Agnes assigned the Duchy of Bavaria, given by her husband to Henry IV, to Otto of Nordheim. This deprived the young king of a solid base of power. Likewise, her decision to assign the Duchies of Swabia and Carinthia to Rudolf of Rheinfelden (who married her daughter) and Berthold of Zähringen, respectively, would prove mistakes, as both later rebelled against the king. Unlike Henry III, Agnes proved incapable of influencing the election of the new popes, Stephen IX and Nicholas II. The Papal alliance with the Normans of southern Italy, formed to counter the communal resistance in Rome, resulted in the deterioration of relations with the German King, as well as Nicholas' interference in the election of German bishops. Agnes also granted local magnates extensive territorial privileges that eroded the King's material power.

In 1062 the young king was kidnapped during a conspiracy of German nobles led by archbishop Anno II of Keulen. Henry, who was at Kaiserwerth, was persuaded to board a boat lying in the Rhine; it was immediately unmoored and the king sprang into the stream, but was rescued by one of the conspirators and carried to Keulen. Agnes retired to a convent, the government subsequently placed in the hands of Anno. His first move was to recognize the Pope Alexander II in his conflict with the antipope Honorius II, who had been initially recognized by Agnes but was subsequently left without support.

Anno's rule proved unpopular. The education and training of Henry were supervised by Anno, who was called his magister, while Adalbert of Hamburg, archbishop of Bremen, was styled Henry's patronus. Henry's education seems to have been neglected, and his willful and headstrong nature developed under the conditions of these early years. The malleable Adalbert of Hamburg soon became the confidant of the ruthless Henry. Eventually, during an absence of Anno from Duitsland, Henry managed to obtain the control of his civil duties, leaving Anno only with the ecclesiastical ones.

[edit] First years of rule and Saxon War

In March 1065 Henry was declared of age. The whole of his future reign was apparently marked by efforts to consolidate Imperial power. In reality, however, it was a careful balancing act between maintaining the loyalty of the nobility and the support of the pope.

In 1066, one year after his enthroning at the age of fifteen, he expelled Adalbert of Hamburg, who had profited off his position for personal enrichment, from the Crown Council. Henry also adopted urgent military measures against the Slav pagans, who had recently invaded Duitsland and besieged Hamburg.

In June 1066 Henry married Bertha of Maurienne, daughter of Count Otto of Savoy, to whom he had been betrothed in 1055. In the same year he assembled an army to fight, at the request of the Pope, the Italo-Normans of southern Italy. Henry's troops had reached Augsburg when he received news that Godfrey of Tuscany, husband of the powerful Matilda of Canossa, marchioness of Tuscany, had already attacked the Normans. Therefore the expedition was halted.

In 1068, driven by his impetuous character and his infidelities, Henry attempted to divorce Bertha[1]. His peroration at a council in Mainz was however rejected by the Papal legate Pier Damiani, who hinted that any further insistence towards divorce would lead the new pope, Alexander II, to deny his coronation. Henry obeyed and his wife returned to Court, but he was convinced that the Papal opposition aimed only at overthrowing lay power within the Empire, in favour of an ecclesiastical hierarchy.

In the late 1060s Henry set up with strong determination to reduce any opposition and to enlarge the national boundaries. He led expeditions against the Liutici and the margrave of a district east of Saxony; and soon afterwards he had to quench the rebellions with Rudolf of Swabia and Berthold of Carinthia. Much more serious was Henry's struggle with Otto of Nordheim, duke of Bavaria. This prince, who occupied an influential position in Duitsland and was one of the protagonists of Henry's early kidnapping, was accused in 1070 by a certain Egino of being privy to a plot to murder the king. It was decided that a trial by battle should take place at Goslar, but when the demand of Otto for a safe conduct for himself and his followers, to and from the place of meeting, was refused, he declined to appear. He was thereupon declared deposed in Bavaria, and his Saxon estates were plundered. He obtained sufficient support, however, to carry on a struggle with the king in Saxony and Thuringia until 1071, when he submitted at Halberstadt. Henry aroused the hostility of the Thuringians by supporting Siegfried, archbishop of Mainz, in his efforts to exact tithes from them; but still more formidable was the enmity of the Saxons, who had several causes of complaint against the king. He was the son of one enemy, Henry III, and the friend of another, Adalbert of Bremen. He had ordered a restoration of all crown lands in Saxony and had built forts among this people, while the country was ravaged to supply the needs of his courtiers, and its duke Magnus was a prisoner in his hands. All classes were united against him, and when the struggle broke out in 1073 the Thuringians joined the Saxons. The war, which lasted with slight intermissions until 1088, exercised a most potent influence upon Henry's fortunes elsewhere.

[edit] Investiture Controversy

Main article: Investiture Controversy

Initially in need of support for his expeditions in Saxony and Thuringia, Henry adhered to the Papal decrees in religious matters. His apparent weakness, however, had the side effect of spurring the ambitions of Gregory VII, a reformist monk elected as pontiff in 1073, for Papal hegemony.

The tension between Empire and Church culminated in the councils of 1074–1075, which constituted a substantial attempt to delegitimate Henry III's policy. Among other measures, they denied to secular rulers the right to place members of the clergy in office; this had dramatic effects in Duitsland, where bishops were often powerful feudatories who, in this way, were able to free themselves from imperial authority. Aside from the reacquisition of all lost privileges by the ecclesiasticals, the council's decision deprived the imperial crown of rights to almost half its lands, with grievous consequences for national unity, especially in peripheral areas like the Kingdom of Italy.

Suddenly hostile to Gregory, Henry did not relent from his positions: after his defeat of Otto of Nordheim, he continued to interfere in Italian and German episcopal life, naming bishops at his will and declaring papal provisions illegitimate. In 1075 Gregory excommunicated some members of the Imperial Court, and threatened to do the same with Henry himself. Further, in a synod held in February of that year, Gregory clearly established the supreme power of the Catholic Church, with the Empire subjected to it. Henry replied with a counter-synod of his own.

The beginning of the conflict known as the Investiture Controversy can be assigned to Christmas night of 1075: Gregory was kidnapped and imprisoned by Cencio I Frangipane, a Roman noble, while officiating at Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome. Later freed by Roman people, Gregory accused Henry of having been behind the attempt. In the same year, the emperor had defeated a rebellion of Saxons in the First Battle of Langensalza, and was therefore free to accept the challenge.

At Worms, on January 24, 1076, a synod of bishops and princes summoned by Henry declared Gregory VII deposed. Hildebrand replied by excommunicating the emperor and all the bishops named by him on February 22, 1076. In October of that year a diet of the German princes in Tribur attempted to find a settlement for the conflict, conceding Henry a year to repent from his actions, before the ratification of the excommunication that the pope was to sign in Swabia some months later. Henry did not repent, and, counting on the hostility showed by the Lombard clergy against Gregory, decided to move to Italy. He spent Christmas of that year in Besançon and, together with his wife and his son, he crossed the Alps with help of the Bishop of Turin and reached Pavia.

Gregory, on his way to the diet of Augsburg, and hearing that Henry was approaching, took refuge in the castle of Canossa (near Reggio Emilia), belonging to Matilda. Henry's troops were nearby.

Henry's intent, however, was apparently to perform the penance required to lift his excommunication and ensure his continued rule. The choice of an Italian location for the act of repentance, instead of Augsburg, was not accidental: it aimed to consolidate the Imperial power in an area partly hostile to the Pope; to lead in person the prosecution of events; and to oppose the pact signed by German feudataries and the Pope in Tribur with the strong German party that had deposed Gregory at Worms, through the concrete presence of his army.

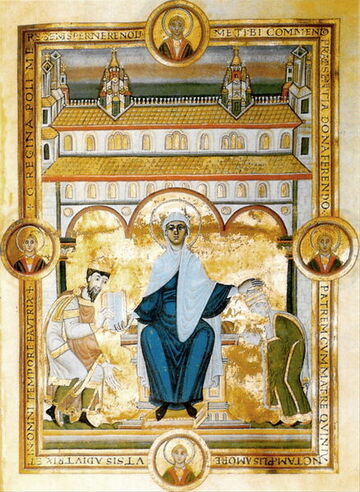

Henry IV begging Matilda of Canossa.He stood in the snow outside the gates of the castle of Canossa for three days, from January 25 to January 27, 1077, begging the pope to rescind the sentence (popularly portrayed as without shoes, taking no food or shelter, and wearing a hairshirt - see Walk of Canossa). The Pope lifted the excommunication, imposing a vow to comply with certain conditions, which Henry soon violated.

[edit] Civil war and recovery

Rudolf of Rheinfeld, a two-time brother-in-law of Henry, took advantage of the momentary weakness of the Emperor by having himself declared antiking by a council of Saxon, Bavarian, and Carinthian princes in March of 1077 in Forchheim. Rudolf promised to respect the electoral concept of the monarchy and declared his willingness to be subservient to the pope.

Despite these difficulties, Henry's situation in Duitsland improved in the following years. When Rudolf was crowned at Mainz in May 1077, the population revolted and forced him to flee to Saxony, where he was deprived of his territories (later he was also stripped of Swabia). After the inconclusive battle of Mellrichstadt (August 7, 1077) and the defeat of Flarchheim (27 January 1080) Gregory instead launched a second anathema against Henry in March 1080. However, the evidence that Gregory's hate had such a personal connotation led much of Duitsland to re-embrace Henry's cause.

On October 14, 1080 the armies of the two rival kings met at the Elster River, in the plain of Leipzig. Rudolf was mortally wounded and died soon afterwards, and the rebellion against Henry lost momentum. Another antiking, Henry of Luxembourg, was fought successfully by Frederick of Swabia, Rudolf's successor in Swabia who had married Henry's daughter Agnes. Henry convoked a synod of the highest German clergy in Bamberg and Brixen (June, 1080). Here Henry had Gregory (dubbed "The False Monk") again deposed and replaced by the primate of Ravenna, Guibert (the antipope Clement III).

[edit] Second voyage to Italy

Henry entered in Pavia and was crowned here as King of Italy, receiving the Iron Crown. He also assigned a series of privileges to the Italian cities who had supported him, and marched against the hated Matilda, declaring her deposed for lese majesty and confiscating her possessions. Then he moved to Rome, which he besieged first in 1081: he was however compelled to retire to Tuscany, where he granted privileges to various cities, and obtained monetary assistance (360,000 gold pieces)[2] from a new ally, the eastern emperor, Alexios I Komnenos, who aimed to thwart the Norman's aims against his empire. A second and equally unsuccessful attack on Rome was followed by a war of devastation in northern Italy with the adherents of Matilda; and towards the end of 1082 the king made a third attack on Rome. After a siege of seven months the Leonine city fell into his hands. A treaty was concluded with the Romans, who agreed that the quarrel between king and pope should be decided by a synod, and secretly bound themselves to induce Gregory to crown Henry as emperor, or to choose another pope. Gregory, however, shut up in Castel Sant'Angelo, would hear of no compromise; the synod was a failure, as Henry prevented the attendance of many of the pope's supporters; and the king, in pursuance of his treaty with Alexios, marched against the Normans. The Romans soon fell away from their allegiance to the pope; and, recalled to the city, Henry entered Rome in March 1084, after which Gregory was declared deposed and Clement was recognized by the Romans. On 31 March 1084 Henry was crowned emperor by Clement, and received the patrician authority. His next step was to attack the fortresses still in the hands of Gregory. The pope was saved by the advance of Robert Guiscard, duke of Apulia, who left the siege of Durazzo and marched towards Rome: Henry left the city and Gregory could be freed. The latter however died soon later at Salerno (1085), not before a last letter in which he exhorted the whole Christianity to a crusade against the emperor.

Henry IV (left), count palatine Herman II of Lotharingia and Antipope Clement III (center), from Codex Jenesis Bose (1157).Feeling secure of his success in Italy, Henry returned to Duitsland.

The Emperor spent 1084 in a show of power in Duitsland, where the reforming instances had still ground due to the predication of Otto of Ostia, advancing up to Magdeburg in Saxony. He also declared the Peace of God in all the Imperial territories to quench any sedition. On March 8, 1088 Otto of Ostia was elected pope as Victor III: with the Norman support, he excommunicated Henry and Clement III, who was defined "a beast sprung out from the earth to wage war against the Saints of God". He also formed a large coalition against the Holy Roman Empire, including, aside from the Normans, the Rus of Kiev, the Lombard communes of Milan, Cremona, Lodi and Piacenza and Matilda of Canossa, who had she remarried to Welf II of Bavaria, therefore creating a concentration of power too formidable to be neglected by the emperor.

[edit] Internecine wars and death

In 1088 Henry of Luxembourg died and Egbert II, Margrave of Meissen, a longtime enemy of the emperor's, proclaimed himself the antiking's successor. Henry had him condemned by a Saxon diet and then a national one at Quedlinburg and Regensburg respectively, but was defeated by Egbert when a relief army came to the margrave's rescue during the siege of Gleichen. Egbert was murdered two years later (1090) and his ineffectual insurrection and royal pretensions fell apart.

Henry then launched his third punitive expedition in Italy. After some initial success against the lands of Canossa, his defeat in 1092 caused the rebellion of the Lombard communes. The insurrection extended when Matilda managed to turn against him his elder son, Conrad, who was crowned King of Italy at Monza in 1093. The Emperor therefore found himself cut off from Duitsland. He could return there only in 1097: in Duitsland his power wall still at its height, as Welf V of Bavaria separated from Matilda and Bavaria gave back to Welf IV.

Henry reacted by deposing Conrad at the diet of Mainz in April 1098, and designating his younger son Henry (future Henry V) as successor, under the oath sworn that he would never follow his brother's example.

The abdication of Henry IV in favour of Henry V from the Cronichle of Ekkehard von Aura.The situation in the Empire remained chaotic, worsened by the further excommunication against Henry launched by the new pope Paschal II, a follower of Gregory VII's reformation ideals elected in the August of 1099. But this time the emperor, meeting with some success in his efforts to restore order, could afford to ignore the papal bana. A successful campaign in Flanders was followed in 1103 by a diet at Mainz, where serious efforts were made to restore peace, and Henry IV himself promised to go on crusade. But this plan was shattered by the revolt of his son Henry in 1104, who, encouraged by the adherents of the pope, declared he owed no allegiance to an excommunicated father. Saxony and Thuringia were soon in arms, the bishops held mainly to the younger Henry, while the emperor was supported by the towns. A desultory warfare was unfavourable, however, to the emperor, who was taken as prisoner at an alleged reconciliation meeting at Koblenz. At a diet held in Mainz in December, Henry IV was forced to resign to his crown, being subsequently imprisoned in the castle of Böckelheim. Here he was also obliged that he had unjustly persecuted Gregory VII and to have illegally named Clement III.

When these conditions became known in Duitsland, a vivid movement of dissension spread. In 1106 the loyal party set up a large army to fight Henry V and Paschal. Henry IV managed to escape to Keulen from his jail, finding a considerable support in the lower Rhineland. He also entered into negotiations with England, France and Denmark.

Henry was also able to defeat his son's army near Visé, in Lorraine, on March 2, 1106. He however died soon afterwards after nine days of illness, while he was guest of his friend Othbert, Bishop of Liège. He was 56.

His body was buried by the bishop of Liege with suitable ceremony, but by command of the papal legate it was unearthed, taken to Speyer and placed in the at that time unconsecrated chapel of Saint Afra that was build on the side of the Imperial Cathedral. After being released from the sentence of excommunication, the remains were buried in the Speyer cathedral in August 1111.

[edit] Evaluation

Henry IV was known for licentious behaviour in his early years, being described as careless and self-willed. In his later life, he displayed much diplomatic ability. His abasement at Canossa can be regarded as a move of policy to weaken the pope's position at the cost of a personal humiliation to himself. He was always regarded as a friend of the lower orders, was capable of generosity and gratitude, and showed considerable military skill.

[edit] Marriages

Henry's wife Bertha died on December 27, 1087. She was also buried at the Speyer Cathedral. Their children were:

Agnes of Duitsland (born 1072), married Frederick I von Staufen, Duke of Swabia.

Conrad (February 12, 1074-July 27, 1101)

Adelaide, died in infancy

Henry, died in infancy

Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor

In 1089 Henry married Eupraxia of Kiev, a daughter of Vsevolod I, Prince of Kiev, and sister to his son Vladimir II Monomakh, prince of Kievan Rus. She assumed the name "Adelaide" upon her coronation. In 1094 she joined the rebellion against Henry, accusing him of holding her prisoner, forcing her to participate in orgies, and attempting a black mass on her naked body.

[edit] Henry IV in fiction

The title character in the tragedy Enrico IV by Luigi Pirandello is a madman who believes himself to be Henry IV.

[edit] Notes

^ Bertha in the meantime had retired to the Abbey of Lorscheim.

^ J. Norwich, Byzantium: The Decline and Fall, 21

[edit] Sources

Gregorovius, Ferdinand (1988). History of Rome in the Middle Ages. Rome: Newton Compton.

Robinson, I.S. (2000). Henry IV of Duitsland 1056-1106.

Preceded by

Henry III German King

formally King of the Romans

1053-1087 Succeeded by

Conrad

King of Italy

1080-1093

Holy Roman Emperor

1084-1105 Succeeded by

Henry V

Preceded by

Conrad I Duke of Bavaria

1053-1054;

1055-1061;

1077-1096 Succeeded by

Conrad II

Preceded by

Conrad II Succeeded by

Otto II

Preceded by

Welf I Succeeded by

Welf I

Duke of Bavaria as Henry VIII, 1055-1061. Coming of age to rule on his own in

1065 after a terrible series of regents, Henry himself was badly prepared for

the job ahead. Henry was only partially successful during his reign, for

while he strengthened the king's position against the nobles by gaining the

support of the peasants, the citizens, and the ministerials, his continuing

battles with the reforming church over investiture ultimately weakened royal

influence over the papacy.

Duke of Bavaria as Henry VIII, 1055-1061. Coming of age to rule on his own in

1065 after a terrible series of regents, Henry himself was badly prepared for

the job ahead. Henry was only partially successful during his reign, for

while he strengthened the king's position against the nobles by gaining the

support of the peasants, the citizens, and the ministerials, his continuing

battles with the reforming church over investiture ultimately weakened royal

influence over the papacy.

Duke of Bavaria as Henry VIII, 1055-1061. Coming of age to rule on his own in

1065 after a terrible series of regents, Henry himself was badly prepared for

the job ahead. Henry was only partially successful during his reign, for

while he strengthened the king's position against the nobles by gaining the

support of the peasants, the citizens, and the ministerials, his continuing

battles with the reforming church over investiture ultimately weakened royal

influence over the papacy.

[alfred_descendants10gen_fromrootsweb_bartont.FTW]

King of Duitsland 1054-1084, Emperor 1084-1106; m. (1) Bertha, dau of Otto. (Weis 45-23)

King of Duitsland (Holy Roman Empire) from 1056 and Emperor from 1084, until his abdication in 1105. He was the third emperor of the Salian dynasty.

Henry was the eldest son of the Emperor Henry III, by his second wife Agnes de Poitou, and was probably born at the royal palace at Goslar. His christening was delayed until the following Easter so that Abbot Hugh of Cluny could be one of his godparents. But even before that, at his Christmas court Henry III induced the attending nobles to promise fidelity to his son. Three years later, still anxious to ensure the succession, Henry III had a larger assembly of nobles elect the young Henry as his successor, and then, on July 17, 1054, had him crowned as king by Herman II, Archbishop of Keulen. Thus when Henry III unexpectedly died in 1056, the accession of the six-year-old Henry IV was not opposed. The dowager Empress Agnes acted as regent.

Henry's reign was marked by efforts to consolidate Imperial power. In reality, however, it was a careful balancing act between maintaining the loyalty of the nobility and the support of the pope. Henry jeopardized both when, in 1075, his insistence on the right of a secular ruler to invest, i.e., to place in office, members of the clergy, especially bishops, began the conflict known as the Investiture Controversy. In the same year he defeated a rebellion of Saxons in the First Battle of Langensalza. Pope Gregory VII excommunicated Henry on February 22, 1076. Gregory, on his way to a diet at Augsburg, and hearing that Henry was approaching, took refuge in the castle of Canossa (near Reggio Emilia), belonging to Matilda, Countess of Tuscany. Henry's intent, however, was to perform the penance required to lift his excommunication, and ensure his continued rule. He stood for three days, January 25 to January 27, 1077, outside the gate at Canossa in the snow, begging the pope to rescind the sentence (popularly portrayed as without shoes, taking no food or shelter, and wearing a hairshirt). The Pope lifted the excommunication, imposing a vow to comply with certain conditions, which Henry soon violated.

In 1088, Henry of Luxembourg, an antiking, died and Egbert II, Margrave of Meissen, a longtime enemy of the emperor's proclaimed himself the antiking's successor. Henry had him condemned by a Saxon diet and then a national one at Quedlinburg and Regensburg respectively, but was defeated by Egbert when a relief army came to the margrave's rescue during the siege of Gleichen. Egbert was murdered two years later (1090) and his ineffectual insurrection and royal pretensions fell apart.

In his last years Henry faced rebellions from his eldest son and his wife. He died at Liège in 1106, "like one falling asleep", after nine days of illness. He was interred next to his father at Speyer.

Henry IV (November 11, 1050 - August 7, 1106) was King of Duitsland (Hol y Roman Empire) from 1056 and Emperor from 1084, until his abdicationi n 1105. He was the third emperor of the Salian dynasty. Henry was th e eldest son of the Emperor Henry III, by his second wifeAgnes de Poit ou, and was probably born at the royal palace at Goslar.His christenin g was delayed until the following Easter so that Abbot Hugh of Cluny c ould be one of his godparents. But even before that, athis Christmas c ourt Henry III induced the attending nobles to promisefidelity to his son. Three years later, still anxious to ensure the succession, Henry III had a larger assembly of nobles elect the young Henry as his succe ssor, and then, on July 17, 1054, had him crowned as king by Herman II , Archbishop of Keulen. Thus when Henry III unexpectedly died in 1056 , the accession of the six-year-old Henry IV was not opposed. The dowa ger Empress Agnes acted as regent.

Henry's reign was marked by efforts to consolidate Imperial power. Inr eality, however, it was a careful balancing act between maintaining th e loyalty of the nobility and the support of the pope. Henry jeopardiz ed both when, in 1075, his insistence on the right of a secular ruler to invest, i.e., to place in office, members of the clergy, especiall y bishops, began the conflict known as the Investiture Controversy. I n the same year he defeated a rebellion of Saxons in the First Battleo f Langensalza. Pope Gregory VII excommunicated Henry on February 22,10 76. Gregory, on his way to a diet at Augsburg, and hearing that Henry was approaching, took refuge in the castle of Canossa (near Reggio Emi lia), belonging to Matilda, Countess of Tuscany. Henry's intent, howev er, was to perform the penance required to lift his excommunication, a nd ensure his continued rule. He stood for three days, January 25 to J anuary 27, 1077, outside the gate at Canossa in the snow, begging the pope to rescind the sentence (popularly portrayed as without shoes, ta king no food or shelter, and wearing a hairshirt). The Pope lifted th e excommunication, imposing a vow to comply with certain conditions, w hich Henry soon violated.